The Story of the Black Loyalists, Pt. 1

Image: Rose Fortune came to Nova Scotia with her family after the American Revolutionary War, likely arriving in Annapolis Royal in June 1784. She earned a living as a "trucker," carrying baggage with a wheelbarrow for passengers travelling on the Saint-John-Digby Annapolis ferry. NOVA SCOTIA ARCHIVES

The Book of Negroes is not merely a ledger. It is a story pressed into parchment—a testament to the brutal arithmetic of freedom. It begins in the waning days of the American Revolution, a conflict that promised liberty but delivered it unevenly. Beneath the quill of British officers, this ledger became something else—a declaration, not of independence, but of survival.

But to understand the ledger, you must understand the world in which it was written—a world where liberty was a word spoken loudly by men who owned slaves. In the streets of Philadelphia, they proclaimed the rights of man, even as chains clinked in the shadows. In the fields of Virginia, tobacco thrived in soil soaked with the sweat of men and women who had no rights at all. The American Revolution was a rebellion wrapped in rhetoric, a fight for freedom built on the backs of the unfree.

It was here, in this cauldron of contradiction, that Lord Dunmore—driven from Williamsburg, his power shrinking by the day—made his desperate gamble. He offered a promise of freedom to any enslaved person who would fight for the Crown. A promise that was not born of justice but of necessity. A promise that lit a fire in the hearts of thousands.

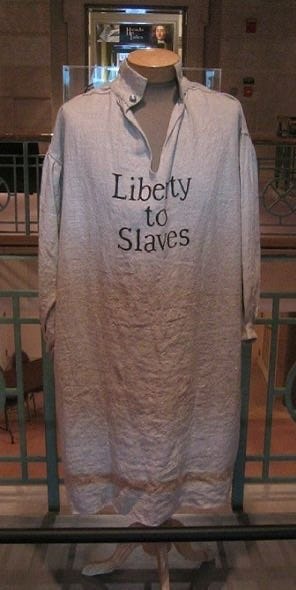

They came to his banner—men and women, barefoot, ragged, desperate. Some were men who had known nothing but labor and the lash. Some were women with children in their arms, fleeing a life of forced servitude. They came with hope, but they came with fear. And when they joined the British lines, they were given uniforms—a bold promise stitched across their chests: “Liberty to Slaves.”

But even as they fought, their freedom was a promise written on water. The Patriots passed laws promising death to any who dared escape. Slaveholders whispered that the British would sell them to sugar plantations in the Caribbean—whispers that were not always lies. Those who fought wore red coats, but the chains of the past still clung to them, invisible but unbroken.

Image: Reproduction of the smock worn by the Royal Ethiopian Regiment formed by Virginia governor Lord Dunmore

And when the war ended, that promise of freedom did not simply dissolve—it hardened into a question. A question that lingered in the docks of New York, the last outpost of a crumbling empire.

What of freedom?

The city was a maze of shadows and rumors, where the triumphant shouts of American independence mingled with the whispered fears of those who had fought for the wrong side.

A Ledger of Life and Loss

The Black Loyalists crowded the docks—thousands of men, women, and children who had wagered everything on a fragile promise. Beneath the roar of celebration—parades, speeches, the triumphant echo of freedom—there was the quieter sound of desperation. The shuffle of feet, the murmurs of those who had been promised liberty but now saw only the gray horizon of the Atlantic.

But for them, freedom was not a gift—it was a transaction. It had to be written down, sanctioned, proven. And so came The Book of Negroes—not a casual record, but a ledger. A collection of names and dates, lines and columns. But beneath the ink-stained parchment is something else—a record of lives caught in the violent churn of a revolution that promised liberty while denying it to many. The entries are stark, clear as a winter plain, each a testament to desperation and defiance.

Image: The Inspection Roll of Negroes, the National Archives, Washington DC.

It was assembled under the direction of Brigadier General Samuel Birch and Sir Guy Carleton, the British Commander-in-Chief in North America. And beneath the dry, bureaucratic language of its entries was a human drama—a diaspora pressed into ink and parchment.

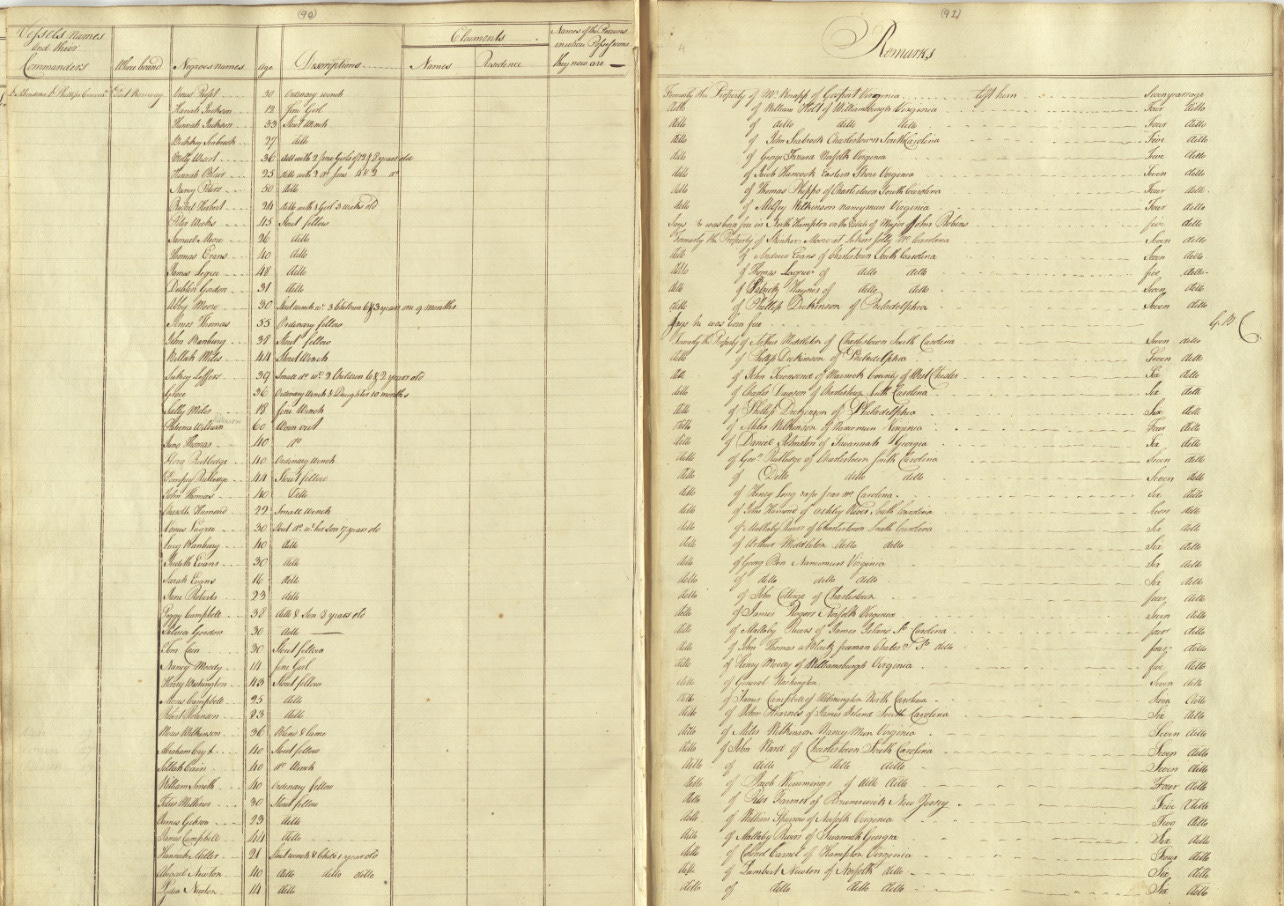

“Harry Washington, 43, fine fellow. Formerly the property of General Washington; left him 7 years ago.” — The Book of Negroes.

Image: Entry of Harry Washington in the Book of Negroes. Source:National archives of Nova Scotia.

Harry Washington. Fine fellow, the ledger says—no other details, just the mark of a man who had once been owned by the most celebrated figure in America. A “fine fellow,” once a servant in the shadow of Mount Vernon’s grand estate, where the air was thick with the smell of tobacco and the quiet rustle of wealth. But Harry had slipped from those shadows—seven years before, he had left Washington’s service. Not as a runaway in the dead of night, but as a Loyalist, a man who saw in the British not masters but liberators. What did he see in those red coats that he did not see in the blue? What calculations did he make when he cast his lot with a king who promised freedom against a republic that spoke of liberty but held his chains?

The Cost of Freedom

But the ledger was more than a list. It was a weapon. For beneath the ink lay a battle of words and wills. The Treaty of Paris (1783) had ended the war, but it had not settled the fate of the Black Loyalists. The Americans demanded the return of all “property”—including the men and women who had seized their freedom. General Washington himself, furious, wrote to Carleton, demanding that no “Negroes” be carried away.

But Carleton refused. Those who had fought for the Crown were not property, he declared. They were free. It was a matter of British honor—but also a final act of imperial defiance. A king who had lost a continent would not be seen as one who broke his word to the lowest of his subjects.

So the ledger grew. Names were written—thousands of them. And those whose names were entered crowded aboard ships, the waves crashing against the hulls as though to remind them that the sea could be as merciless as the masters they fled.

But Nova Scotia, the promised land of sanctuary, became a land of struggle. The soil was rocky, the winters brutal. Land grants were delayed or denied. Hunger stalked the settlements, and prejudice crossed the Atlantic with them. The promise of freedom hardened into a bitter reality. In 1784, in Shelburne, white Loyalists rioted, attacking their Black neighbors, tearing apart the fragile promise of liberty.

And yet they endured. Those who had once been property demanded to be recognized as people.

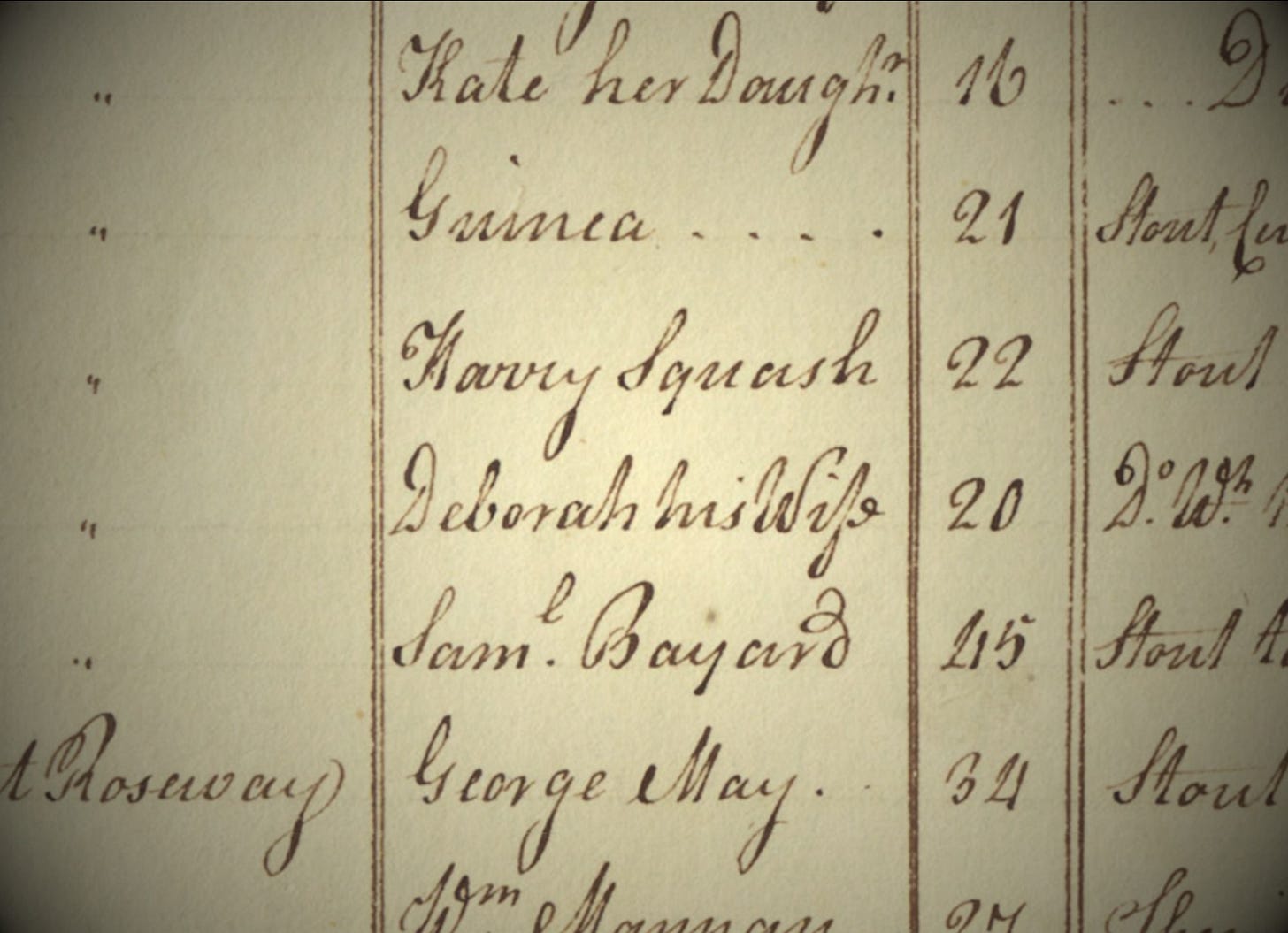

“Deborah, 20, pock-marked, formerly the property of George Washington; left him 4 years ago.” — The Book of Negroes.

Image: Entry of Deborah Squash in the Book of Negroes. Credit: Library and Archives Canada. Original Author: Guy Carleton

Deborah Squash. Her name is there—Deborah—followed by a detail meant to mark her but instead revealing the ledger’s cruelty: “pock-marked.” A woman reduced to a blemish, to a feature meant to diminish. But Deborah’s story is not her scars—it is her escape. Four years before, she had fled from Mount Vernon, from the manicured lawns and the columns that loomed like sentinels. She had seized the chaos of revolution as a chance, the promise of the British as a lifeline. To flee was to gamble everything, to leave a life of certainty—however brutal—for a chance at freedom that was no certainty at all. But she had taken that chance. Her name now on a list of the free.

“Moses Wilkinson, 36, blind and lame, formerly the property of Miles Wilkinson; left him 6 years ago.” — The Book of Negroes.

Moses Wilkinson. Blind and lame—another cruel summation. But the ledger’s ink cannot capture the truth of this man. Daddy Moses, they called him, a preacher whose voice became a flame. He left the plantation not just for freedom of the body but for freedom of the spirit. He had crossed the seas to Nova Scotia, leading his congregation, his sermons thunderous even as his sight was gone. And when those shores proved cold, when the promise of British freedom turned to neglect, he led again—to Sierra Leone, where he built the first Methodist church, his faith a fortress against the world’s indifference. Blind and lame, they called him. But his vision reached further than most.

Image: Congregants of the Shelburne Methodist Episcopal Church (1873-1940s), the "spiritual descendant of Moses Wilkinson's original congregation.

Memory Inscribed in Ink

These names, more than 3,000 of them, survived—testifying to a diaspora born of revolution, a community of the abandoned who carved lives from rock and frost.

They were alive. And their names were written.

The ledger was copied, its pages folded into British archives—an artifact of imperial paperwork. But it was also something more—a silent archive of human dignity. Each name, a voice that refused to be silenced.

“William Homes, 24, formerly the property of Robert Morris; left him 5 years ago.” — The Book of Negroes.

Image: William Homes in the "Book of Negroes" - July 31, 1783, Independence National Historical Park

William Homes, a name etched in the ledger, a name once owned by Robert Morris—signer of the Declaration, financier of the Revolution. To the Americans, Morris was a patriot; to William, he was a master. And when the war came, when the rhetoric of liberty rose like a tide, William saw an opening. He left Morris, not just in body but in allegiance. He cast his lot with the British, choosing the uncertain promise of a distant crown over the false promise of a republic built on bondage. His name, too, is inked here—a record of defiance, a mark of a life reclaimed.

Decades passed. The pages yellowed, the ink faded. But The Book of Negroes survived. It would be pulled from forgotten shelves, read again, its silent voices heard. Those who had stood at the edge of the Atlantic, watching the ships sail, had dared to declare their existence. And we, who read their names now, are witnesses to that defiance.

They crossed an ocean for a fragile promise of freedom. Some found it. Many did not. But they insisted on being remembered.

Primary Sources

Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, 1775. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/lord-dunmores-proclamation-1775.

Nova Scotia Archives. Black Loyalists, Nova Scotia. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://novascotia.ca/archives/virtual/africanns/loyalists.asp.

Searchable Museum. “Service with the British.” Accessed May 14, 2025. https://www.searchablemuseum.com/service-with-the-british

The Canadian Encyclopedia. “The Shelburne Riots.” Accessed May 14, 2025. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/the-shelburne-race-riots.

The National Archives (UK). The Book of Negroes. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://beta.nationalarchives.gov.uk/explore-the-collection/stories/the-book-of-negroes/.

U.S. National Archives. Treaty of Paris (1783). Accessed May 14, 2025. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/treaty-of-paris.

Secondary Sources

Cooper, Afua. The Hanging of Angelique: The Untold Story of Canadian Slavery and the Burning of Old Montreal. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

Nash, Gary B. The Forgotten Fifth: African Americans in the Age of Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Pybus, Cassandra. Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006.

Schama, Simon. Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution. New York: Ecco Press, 2006.

Walker, James W. St. G. The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783-1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Websites

Grandy, Leah. “The Importance of the Book of Negroes.” Atlantic Loyalist Connections, University of New Brunswick Libraries. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://loyalist.lib.unb.ca/atlantic-loyalist-connections/importance-book-negroes.

Black Loyalist: Our History, Our People “Black Loyalist: Our History, Our People.” Canada’s Digital Collections. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/index.htm.