The Story of the Black Loyalists, Pt. 3

Image: Temporary shelters the Black Loyalists lived in upon their arrival in Nova Scotia in 1783. Black Loyalists Heritage Center, Nova Scotia.

They landed with nothing but their names, their memories, and the inked promise of liberty—names logged by British officials in New York, names which had once belonged to property now claimed by themselves. In the summer of 1783, the Black Loyalists arrived in Nova Scotia not as refugees but as free men and women. Or so they were told. They had staked everything on the loyalty of an empire that had used them to bleed a continent dry of rebellion. And now, on these northern shores, they came seeking a new beginning—some still wearing the tattered uniforms of the Black Pioneers, others with children in tow, all with histories of bondage pressed into the muscle of their backs and the callouses of their hands.

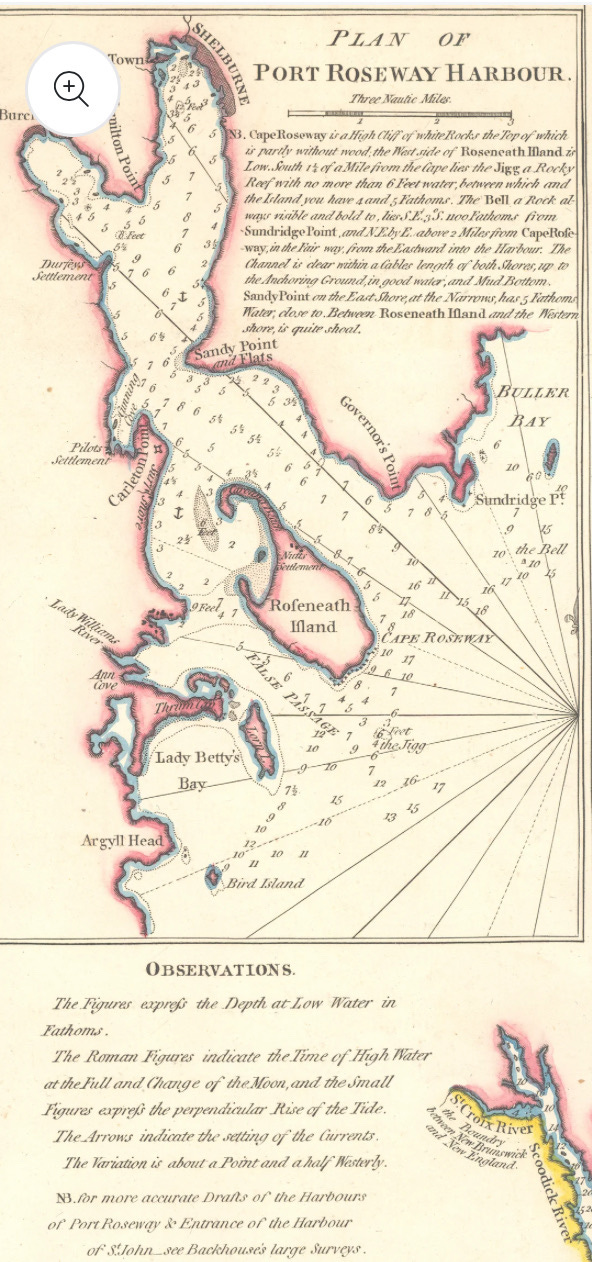

They disembarked in Port Roseway, a port that would be rechristened Shelburne, only to find themselves exiled again—this time to the rocky, forest-choked margins of that settlement, to a place soon called Birchtown. It was land granted, but only nominally: swamp at its rear, stones at its feet, and the cold Atlantic pressing in from the bay. Birchtown may have been named for General Birch, the British officer who had authorized their evacuation, but there was little of shelter or shade in the naming. It was less a town than a gesture.

Image: Detailed inset map of Burch Town (Birchtown) and the black suburb of Shelburne. Published London 12 July 1798, Cartographer: Captain Holland, Nova Scotia Archives.

The work began immediately. With no nails, few tools, and promises still drifting like fog over the harbor, the Black settlers built what they could: dugouts covered with timber scraps, huts of wattle and daub, cone-shaped shelters tied with birch bark. Their knowledge of building came not from books or blueprints but from plantation quarters and military trenching—adapted now, poorly, to northern latitudes they had never known. And as they labored to construct homes from forest and frost, they were denied the timber that had been stockpiled in nearby Shelburne, denied the farm plots that white settlers had claimed for themselves.

For three days each week, they were conscripted for public works in exchange for food: clearing trees, digging roads, laying the rough lines of empire. The rest of the week, they scrounged for sustenance. Colonel Stephen Blucke, once their commanding officer, became their reluctant intermediary—respected by British officials, but distrusted by many in Birchtown, who saw him as too closely tied to the authorities who kept their community in a state of enforced dependency. Still, Blucke’s Black Pioneers became the only source of paid employment in the town—if one could call the pittance “pay.”

As early as 1784, the encirclement of Black land began. Surveyors acting in the interests of white settlers sliced off large sections of Birchtown’s northern tract. Land for the Anglican Church took what lay eastward. And slowly, then more overtly, white settlers seized terrain that had never been offered to Black Loyalists to begin with. Promised 40 or 50 acres, many Black settlers received far less—or nothing. They were penned in by land grants they could not access, and watched, helpless, as lumber-rich homes were seized for tax arrears and torn down rather than offered to Black laborers in need of shelter.

Image: Reconstruction of Black settlers shelters after arriving in Nova Scotia. Black Loyalists Heritage Center.

The same pattern repeated itself across the province. In Guysborough, a fire destroyed the initial Black settlement in 1784, and the survivors were relocated to remote and infertile Tracadie—3000 acres of scrub and stone that was better than nothing, and often little more. In Digby, Brindley Town was built, then displaced, then built again, each move set in motion by the bureaucracy of dispossession. In Preston, near Halifax, the proximity to markets offered a faint opportunity—until even there, sharecropping tethered Black settlers to white landowners whose titles outranked their toil.

By 1792, Birchtown still looked much as it had a decade earlier: a sprawl of huts, temporary shelters made permanent by neglect. Governor John Clarkson, visiting that year, wrote of the squalor with a mixture of pity and bureaucratic alarm. He found them still in rags, still in huts with no stoves or insulation, and still waiting for the land and liberty they had fought for.

Some left. Many, in fact. That same year, more than 1,200 Black Loyalists boarded ships again—this time bound for Sierra Leone, where Clarkson promised a new settlement in Africa, free of white interference. For those who remained, what had begun as a vision of equality hardened into the reality of apartheid-by-survey. They were no longer Loyalists; they were tenants. And then, they were tenants without title. They became what the empire had always feared they would become: permanent reminders that freedom, once granted, could not be contained.

Image: The historic Black community of North Preston, on Oct. 2, 1934. Photo courtesy: Nova Scotia Archives.

Yet they stayed. And in the shallow soil and chill fog of Nova Scotia, they built communities that still exist: Tracadie, Digby, East Preston. Their descendants carry the names of those who arrived with the evacuation fleet and lived through the second exile. And in those names, and the memory of Birchtown’s huts, there remains a trace of that first spring—a moment when the future seemed possible, even if the land beneath their feet would not hold it.

Primary Sources

British Government. Book of Negroes. 1783. Nova Scotia Archives. Accessed May 28, 2025.

https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/book-of-negroes/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3070438?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Clarkson, John. The Clarkson Papers. Edited by Kenneth C. Barnes. London: Hakluyt Society, 1998.

https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/mission/153-155.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://equianosworld.org/associates-abolition.php?id=9&utm_source=chatgpt.com

Colonial Office Records. Nova Scotia Correspondence and Land Grants. CO 217. The National Archives (UK).

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C4408

Shelburne Muster Rolls and Blucke Papers. 1783–1791. Nova Scotia Archives and Shelburne County Museum Collections.

https://loyalist.lib.unb.ca/record/local-records-1782-1860

Fergusson, Charles Bruce, ed. Clarkson's Mission to America, 1791-1792. Publication No. 11. Halifax: Public Archives of Nova Scotia, 1971.

https://archives.novascotia.ca/african-heritage/archives/?ID=686

Hodges, Graham Russell, ed. The Black Loyalist Directory: African Americans in Exile after the American Revolution. New York: Garland for the New England Historical Genealogy Society, 1995.

https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/6919744

MacNutt, W. S. Select Loyalist Memorials: The Appeals for Compensation for Losses and Sacrifices to the British Parliamentary Commission of 1783 to 1789 from Loyalist of the American Revolution who came to Canada. Typescript. University of New Brunswick Archives and Special Collections. See https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/americanloyalists.pdf

Stephen Blucke’s Leadership in Birchtown.

https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/people/secular/blucke.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Secondary Sources

Barry Cahill, “The Black Loyalist Myth in Atlantic Canada”, Acadiensis, XXIX, 1, (Autumn 1999),pp.76-87.

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/download/10801/11588/14683

Schama, Simon. Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution. New York: HarperCollins, 2006.

Walker, James W. St. G. The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993.

Whitfield, Harvey Amani. “Black Loyalists and Black Slaves in Maritime Canada.” Acadiensis (2012).

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/acadiensis/article/view/20066/23079

Whitfield, Harvey Amani. North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016.

Winks, Robin W. The Blacks in Canada: A History. 2nd ed. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000. See

https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/SCMicroR5858.pdf

Further Reading