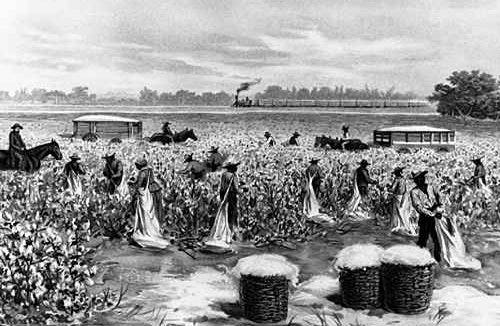

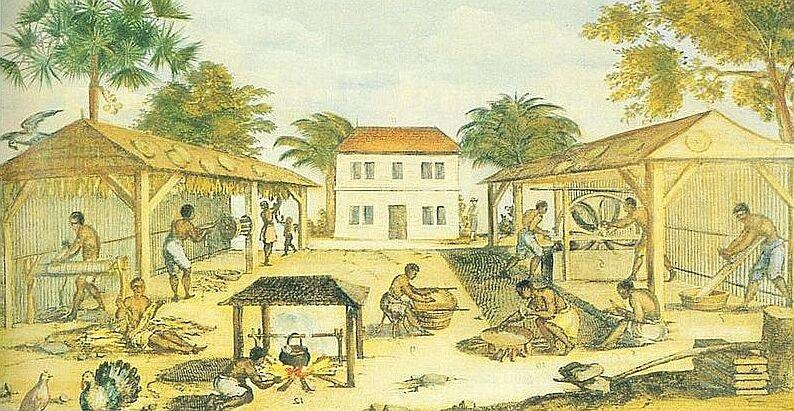

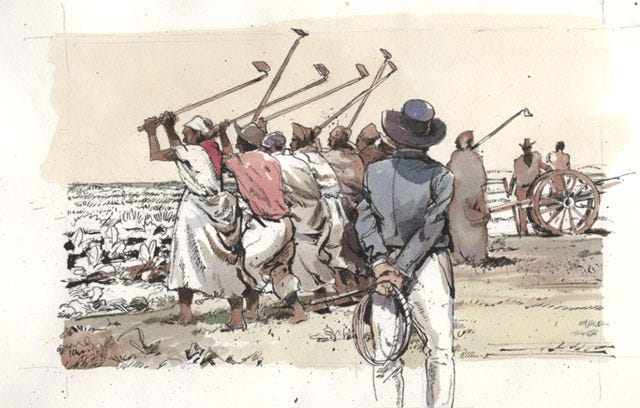

Although they may have sounded like meaningless noise to many white observers, for the enslaved individuals, Field Hollers, work songs, Shouts, and cries held immense significance. They were everything. As Black Americans toiled in the cotton, tobacco , and rice fields, work songs and field hollers provided a lifeline of emotional release and camaraderie.

Each holler, shout, and cry conveyed different messages, often acting as encrypted codes, retelling Bible stories, and delivering messages of hope. Beyond their musical function, these songs became a powerful deliverance from despair, offering solace and a sense of community amidst the dehumanizing conditions of slavery.

The melodies of field hollers and work songs bore witness to the resilience and endurance of the enslaved, forging a cultural legacy that continues to impact and inspire musicians and listeners worldwide.

Around 1860, the United States had approximately 4,000,000 slaves. Among the 15 slaveholding States, there were 12,210,000 inhabitants, with 8,039,000 being White, 251,000 free colored persons, and 3,950,000 being slaves. The American South, relying on slave labor, played a significant role in global cotton production during that era.

Despite enduring back-breaking, sun-up-to-sundown hard labor, slaves had to find some solace in their lives. Stripped of everything they owned, they displayed remarkable resilience, intertwining their culture into their newly acquired lifestyle. Religion served as a strong force, allowing them to preserve essential aspects of their cultural identity.

Beyond their musical function, these songs became a powerful deliverance from despair, offering solace and a sense of community amidst the dehumanizing conditions of slavery.

Indeed, many work songs and field hollers originated from religious influences, while others conveyed intense emotions through stories of their life experiences. Shouts, calls, and hollers, however, had distinct purposes.

Shouts and calls were often directed at specific individuals or to signal important messages, even encoded information about the proximity of a white owner. On the other hand, hollers were more general expressions, not targeted at anyone or anything in particular.

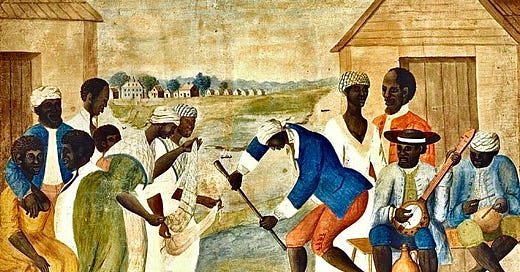

From the 17th to the 19th centuries, labor and field songs emerged, evolving into a unique musical style within the African Diaspora. They were deeply rooted in the oral tradition of African music, sung by slaves during plantation work, communal worship, or social gatherings.

Work songs, enriched with biblical parables, coded messages, and motivational lyrics, served to pass the time during mundane tasks like harvesting and planting. These songs combined singing with rhythmic and physical activities, also being used to wake up sleepy fellow slaves or to express emotions while working.

Hollers, filled with meaningful sounds, accompanied by rhythmic movements and powerful words, could be heard by those in close proximity. Working and singing became intertwined, contributing to the continuity of the African diaspora. Hollers and other empowering musical forms became the building blocks for future generations to embrace and carry on the freedom struggle.

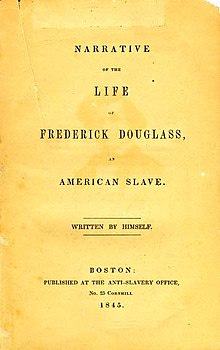

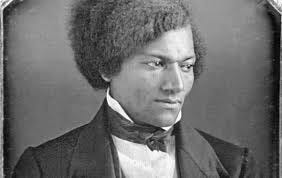

In “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,“ Frederick Douglass writes expressively of these heartrending lamentation:

“The slaves selected to go to the Great House Farm, for the monthly allowance for themselves and their fellow-slaves, were peculiarly enthusiastic. While on their way, they would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness.”

“They would compose and sing as they went along, consulting neither time nor tune. The thought that came up, came out—if not in the word, in the sound;—and as frequently in the one as in the other. They would sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone.”

“Into all of their songs they would manage to weave something of the Great House Farm. Especially would they do this, when leaving home. They would then sing most exultingly the following words:— “I am going away to the Great House Farm! O, yea! O, yea! O!”

“This they would sing, as a chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.”

“I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle; so that I neither saw nor heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. “

“Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them. The mere recurrence to those songs, even now, afflicts me; and while I am writing these lines, an expression of feeling has already found its way down my cheek.”

“ To those songs I trace my first glimmering conception of the dehumanizing character of slavery. I can never get rid of that conception. Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds.”

“If any one wishes to be impressed with the soul-killing effects of slavery, let him go to Colonel Lloyd's plantation, and, on allowance-day, place himself in the deep pine woods, and there let him, in silence, analyze the sounds that shall pass through the chambers of his soul,—and if he is not thus impressed, it will only be because “there is no flesh in his obdurate heart.”

“I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their Contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. “

“The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy, and singing for joy, were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. “

“The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness, as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion.“

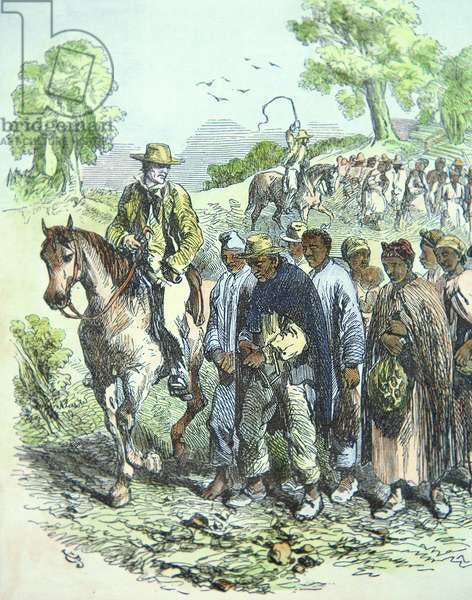

On the other hand, White people living, working , or visiting plantations mostly remained clueless:

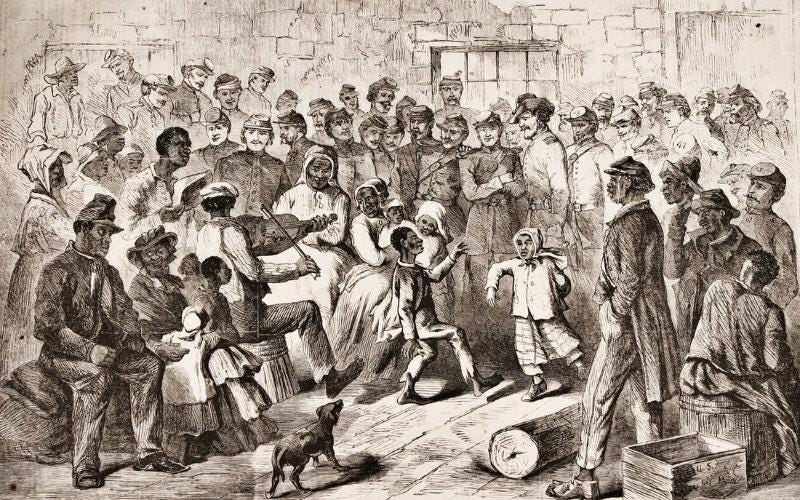

In his 1848 diary, while commenting on the lucrative trade for hogs, wheat, butter, horses, cows, and produce such as beans and corn, a white merchant in Murfreesboro Tennessee, John Spence, described the sale of enslaved people thus:

“. . . A Negro in his servitude was happy and contented, when he had a kind benevolent master to look after his wants . . . They were provided good cabins for themselves and the families, slavery and freedom, words little understood by them. They were possessed of light hearts, light minds and moderate wants in everything.”

“A Negro’s heaven, allow him to have a wife, a few miles from home to visit of Saturday nights, a truck patch of his own, a few dollars, pocket money for Christmas spending, then a Banjo, fiddle or some article for music. He was rich and happy . . .”

This is a striking (but not unsurprising) example of the narrative of benevolence and paternalism that ran rampant throughout the antebellum South

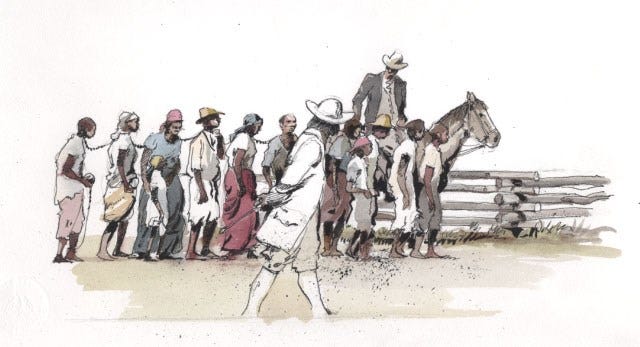

The enslaved literally had to sing to keep their sanity. Songs with hidden meanings infused every part of life. From their capture in Africa to their servitude in America, slaves were forcibly forbidden to use any instruments. One has to marvel at the creative adaptation to clapping and jumping as well as stomping rhythmically.

The slave call-and-response melodies were adapted to spirituals, field hollers and work songs, becoming a cultural influence on every aspect of American music today.

A moan or groan in the music expressed the pain, an emotional expression communicating the real story, a cry for freedom and a better way of life.

Despite their exceedingly grim conditions as slaves and even after the Civil War, many continued to share their dreams musically, setting the process in motion for freedom which would continue in song through the 1960s Civil Rights movement.’

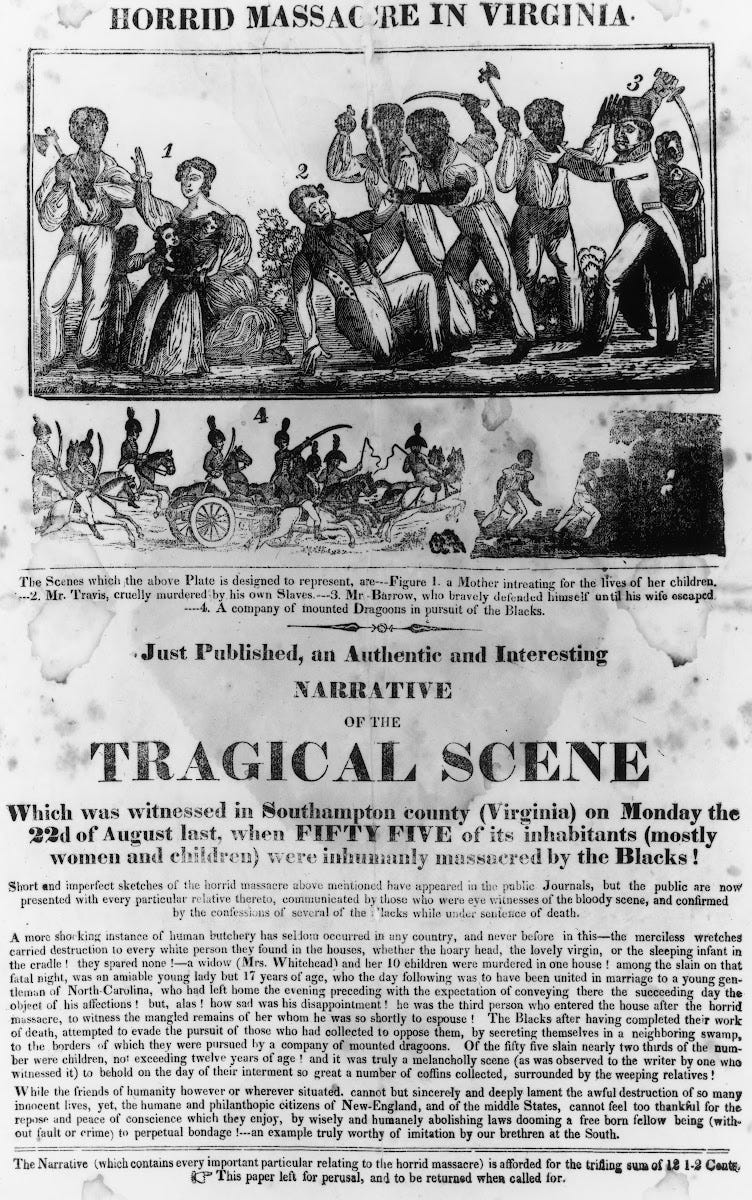

In August of 1829, news from North Hampton, Va., reverberated across the nation; a slave uprising had been initiated by a slave named Nate Turner. This insurrection spread panic in the hearts of White Americans. Across Southern plantations, slaveowners, bent on retaining control, formed patrols with guards making continuous rounds night and day, ensuring that the rebellion did not spread.

Soon news came that Nate Turner had been caught in Virginia and was subsequently hanged. Black Americans’ reactions were muted:

A firsthand account of the reaction by the slaves in the one community once word reached them:

“The cloud removed, the sun gradually assuming his usual brightness, the people were more cheerful. The Negroes were not looked after with the same distrust. They were going singing, whistling and loud laughing . . .”

Perhaps the emotional response to Turner's rebellion concealed the seeds of messages of emancipation.

Example of a work song

Example of a field holler

Kaleo: Example of Modern music influenced by field hollers, cries, work songs, and shouts

Larry McCray: Blues Influenced by Call and Response

Resources

https://blackmusicscholar.com/field-hollers-and-work-songs/

https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/slavery/experience/education/history.html

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000058/

https://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.25385/?sp=31&st=single

Books

John Spence, Annals of Rutherford County vol. 2 (The Rutherford County Historical Society, 1991) 20.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave,Boston: Published at the Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.