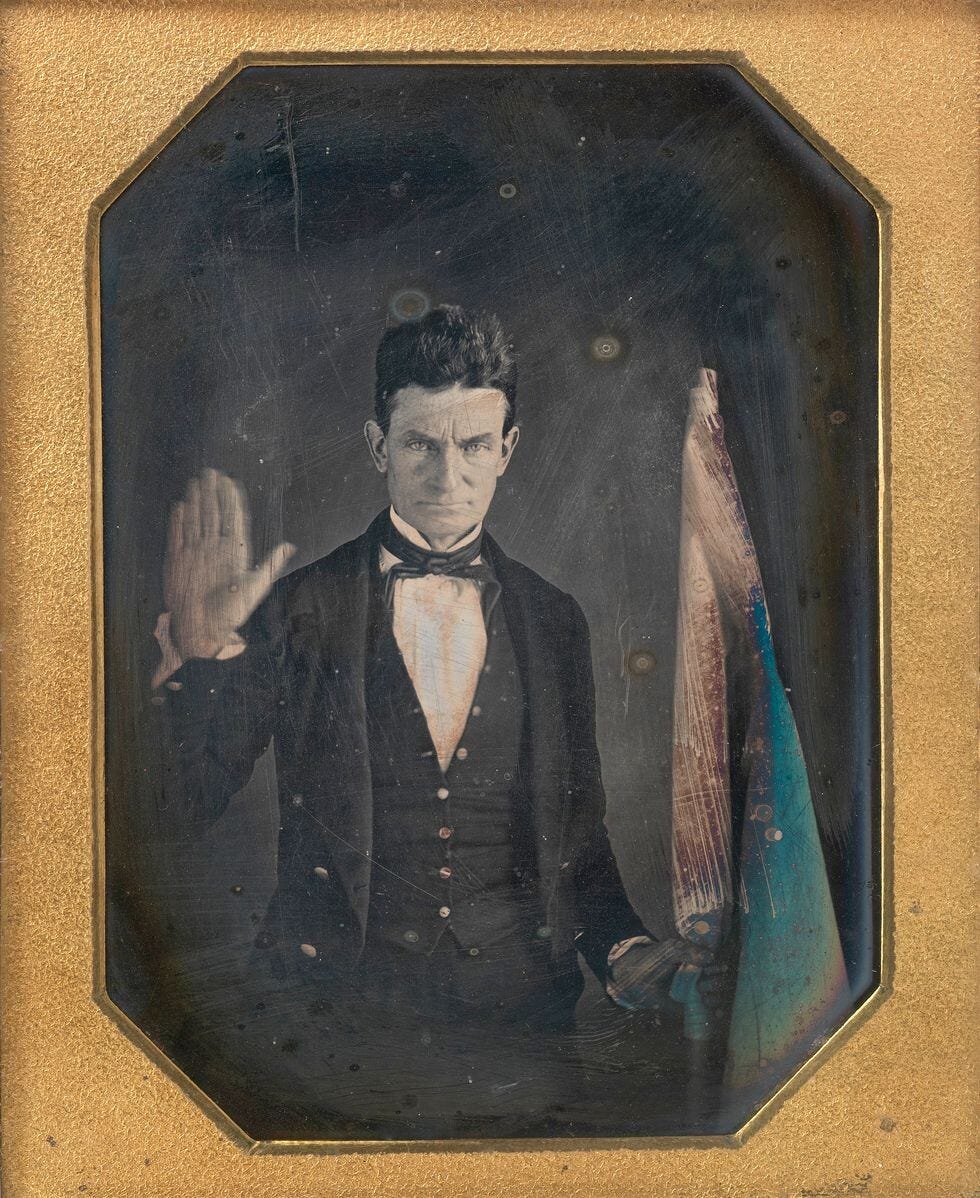

John Brown and Frederick Douglass were two of the most prominent abolitionists of the 19th century. Brown was known for his militant tactics in the fight against slavery, while Douglass was a former slave who became a powerful orator and writer advocating for the end of slavery. Although they shared the same goal, their approaches were vastly different, and their relationship was often strained. In fact, John Brown's actions almost got Frederick Douglass killed.

Frederick Douglass, who first encountered John Brown in 1847, had a complex relationship with the passionate abolitionist throughout the late 1850s. Brown was not an easy person to love, but everything changed when he met his fate on the gallows.Despite a mixture of admiration and ambivalence, Douglass recognized Brown's visionary nature.

The relationship between John Brown and Frederick Douglass was marked by Brown’s militant and violent stance against slavery, which greatly influenced Douglass’ own radicalism in the 1850s. However, Douglass remained wary of Brown due to his secretive nature and strategic ineptness, especially when Brown implored Douglass to join the Harpers Ferry raid.

Their first meeting occurred in 1847 at Brown’s home in Springfield, Massachusetts, bringing together two renowned abolitionists of the 19th century. While Douglass was already famous for his background as an enslaved person and his escape from captivity, it was Brown, a white man with failed business endeavors and unwavering religious conviction, who appeared more determined to put an end to the cruel institution of slavery.

Douglass, in his 1881 autobiography “Life and Times of Frederick Douglass,” recalled being impressed by Brown’s physical stature—his lean, strong, and sinewy build—and noticed how his children held him in reverence. However, it was Brown’s impassioned words that left the strongest impression, as he detailed a plan to liberate the enslaved and guide them to freedom through the Alleghany Mountains.

Brown demonstrated careful consideration by providing measured responses to Douglass’ inquiries. He explained that armed men would be stationed at strategic checkpoints, ready to descend into towns to rally the enslaved and secure provisions. Even if they were cornered by authorities, Brown believed that dying for such a noble cause would be a fitting end.

Douglass, initially a supporter of Garrison's non-resistance abolitionism, underwent a transformation in his beliefs after spending a night at Brown's home. The encounter left him increasingly skeptical of the peaceful abolition of slavery, and his speeches and writings began to reflect Brown's strong convictions.

In his autobiography, Douglass wrote:

“While I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful of its peaceful abolition…My utterances became more and more tinged by the color of this man's strong impressions."

Meanwhile, Brown's involvement in the violent "Bleeding Kansas" conflicts elevated his national profile, earning admiration from those who believed that only bloodshed could end slavery. Douglass, who encountered Brown frequently during this tumultuous period, grew to hold a more favorable impression of him and developed a deeper respect for his character.

Douglass wrote:

“I met him often during this struggle and all I saw of him gave me a more favorable impression of the man, and inspired me with a higher respect for his character."

Brown frequently stayed with Douglass during his trips back east to acquire money and arms during the late 1850s.

In late January 1858, John Brown visited Frederick Douglass's home in Rochester, New York, where he stayed for a month. During this secluded period, Brown worked on drafting his "provisional constitution" for Virginia, intending to overthrow the state through his raid on Harpers Ferry's federal arsenal in Virginia.

Despite Douglass's growing militancy, he still believed in the significance of political action to bring an end to slavery, which put him at odds with Brown's increasing radicalism. In March 1859, both men, along with other abolitionist leaders, convened at William Webb's home in Detroit. However, they were unable to resolve the stalemate arising from their differing views.

Although Douglass was intrigued by the clandestine plotters against slavery, he did not attend Brown's "convention" in Chatham, Ontario, on May 8, 1858, where Brown sought to recruit African Americans to join his cause. Douglass also had two encounters with Hugh Forbes, an Englishman hired by Brown as his military strategist, during Forbes' visits to Rochester in 1857-1858.

However, Douglass found Forbes to be unreliable both with finances and personal trust. John Brown and his plans held a captivating allure and a glimmer of hope, but he remained a challenging figure to truly love.

Brown and Douglass met for the final time at a quarry near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in August 1859. This time, Brown presented the full scope of his plan to capture the federal armory at the Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and arm the enslaved for a major insurrection.

Sitting on large rocks, Brown and Douglass engaged in a discussion about Brown's plans. Brown earnestly implored Douglass to join his small group of dedicated warriors, expressing a specific purpose for his involvement. Douglass recalled Brown's words, "I want you for a special purpose... When I strike, the bees will begin to swarm, and I want you to help hive them."

However, Douglass was disheartened by the shift in Brown's intentions. He had initially understood that Brown aimed to free slaves in Virginia and guide them to safety in the Appalachian Mountains. Yet now, Brown seemed fixated on attacking the federal arsenal, a move Douglass deemed desperate and mistaken.

Despite Douglass's warning about the perilous nature of the plan, Brown brushed off the concerns and continued to press for Douglass's participation.While Douglass ultimately declined Brown's pleas, he allowed his companion, Shields Green, to make his own decision. Douglass recounted that Green responded, "I believe I'll go with the old man," willingly accepting the fate of dying at Harpers Ferry.

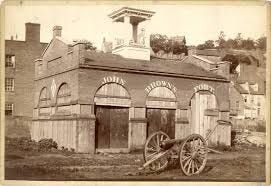

After declining to join the ill-fated Harpers Ferry raid on October 16, 1859, Frederick Douglass anxiously awaited news of the attack. The nation was electrified by reports of the assault on the federal arsenal at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. The raid ended in disaster, with most of the participants either captured or killed.

Following Brown's arrest, a letter from Douglass to the old warrior, written in 1857, was among the documents seized. This led outraged Virginians to potentially view Douglass as a co-conspirator in Brown's actions. Douglass, who was lecturing in Philadelphia at the time news of the raid reached him, hastily returned home to Rochester, fearing that if caught and sent to Virginia, he would be killed for being Frederick Douglass.

While it is likely that Brown shared more details of his revolutionary plans with Douglass than the orator admitted publicly, Douglass never found Brown's plans or leadership convincing. There is some dispute about the accuracy of Douglass's version of events.

John E. Cook, one of Brown's captured men, claimed that Douglass had reneged on a promise to bring additional men to the raid. Brown, refusing to implicate his associates before his death sentence, reportedly expressed frustration to a friend, attributing the missed opportunity at Harpers Ferry to "the famous Mr. Frederick Douglass."

Accused of being tied to a man facing treason charges, Frederick Douglass defended himself in an October 31 letter to the Rochester Democrat and American. He vehemently denied making any promises to join the raid and clarified that he never encouraged or supported the takeover of Harpers Ferry. However, aware of the trouble he faced due to his public association with the accused, Douglass left for England in November.

Under the cloud of suspicion, Douglass and feeling the need to defend himself against accusations of treason and betrayal, Douglass wrote a public letter before departing Canada, rejecting Cook's denunciation and affirming that he never made commitments to participate in the raid and had not endorsed the attack on the United States Arsenal.

He declared that the “taking of Harpers Ferry was a measure never encouraged by my word or by my vote. . . . My field of labor for the abolition of slavery has not extended to an attack on the United States Arsenal.”

In the cover of darkness on October 22, with an arrest warrant issued and federal marshals closing in on his upstate New York hometown, Douglass embarked on a ferry across Lake Ontario, a route he had once guided many escaped slaves through.

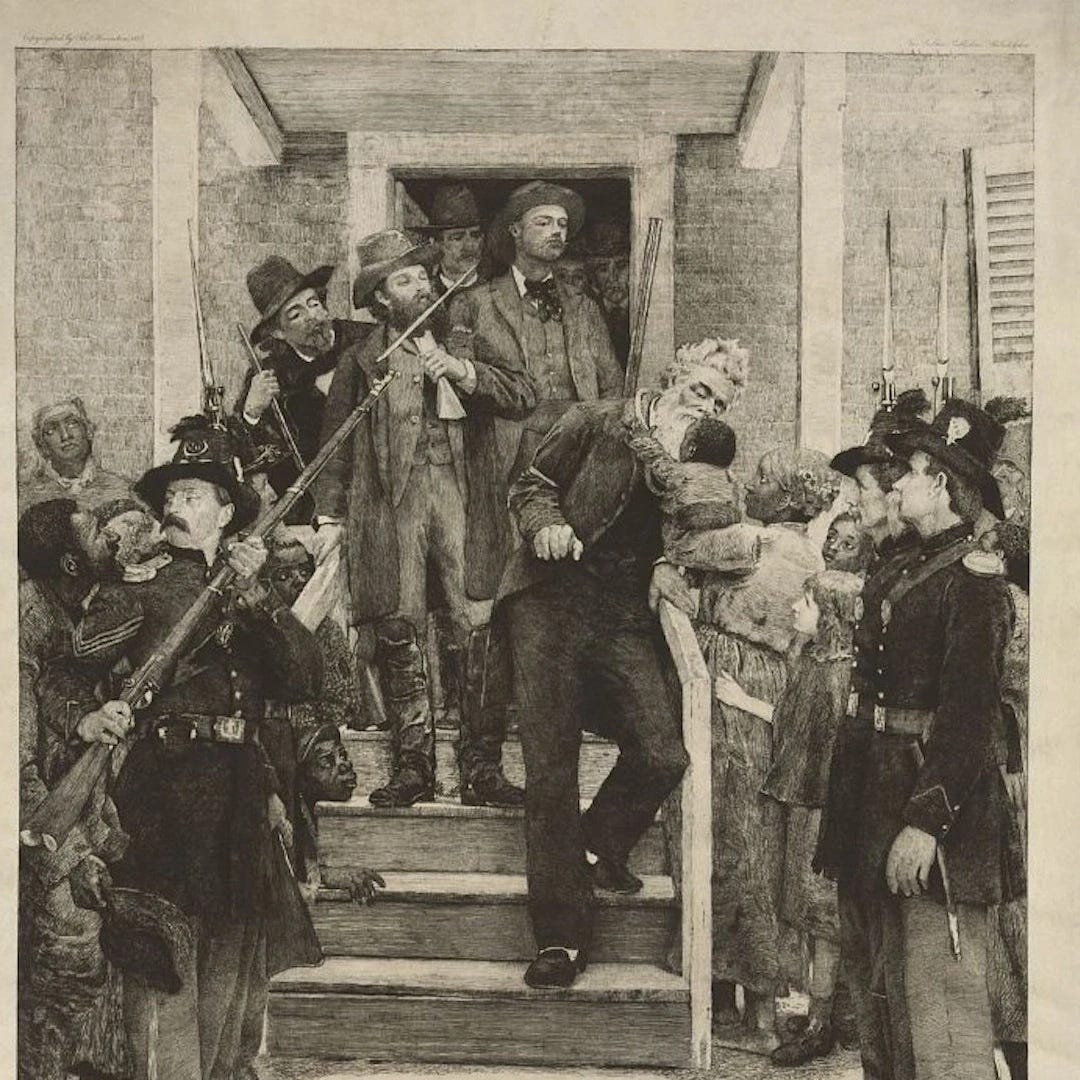

John Brown and his remaining accomplices were executed on December 2, 1859, for treason, murder, and inciting slave insurrection. Faced with anxiety and limited options, Douglass embarked on a lecture trip to England, a journey he had previously planned but now undertaken in unexpected circumstances.

There is no doubt that Frederick Douglass, while advocating for his legal innocence, embraced violence and positioned himself as a moral ally of John Brown. This perspective became common among abolitionists, including some Republican politicians. Douglass expressed his readiness to take action against slavery through various means, such as writing, speaking, publishing, organizing, and even conspiring, as long as there was a reasonable hope of success.

Douglass believed that those who deprived others of their labor and freedom had forsaken justice and honor, becoming akin to thieves and pirates.Importantly, Douglass clarified that his objection was not to Brown's ultimate goals or justifications, but rather to his specific methods and tactics.

He highlighted that even Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel, "Uncle Tom's Cabin," demonstrated the necessity of lawlessness as a weapon for abolitionists. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 had turned virtually all radical abolitionists into law-breakers.

Douglass was willing to defy the law and even kill those he deemed as "pirates." However, he recognized that effectively combating slavery and its pervasive influence required more than courage and justification; it demanded exceptional cunning, skill, mobilization, and military prowess.

Returning to America from England in 1860 after the loss of his beloved daughter Annie, Douglass found his family in mourning and the nation on the verge of disunion. Within his arsenal of rhetorical weapons against slavery and, soon, the Confederacy, John Brown's death remained a powerful symbol.

Despite Brown's challenging nature during his lifetime, his significance in death was undeniable. The Brown family, however, harbored bitterness towards Douglass, feeling betrayed by his actions.

Upon his return to a country on the brink of civil war the following summer, Douglass recognized the value of invoking Brown as a martyr for the anti-slavery cause and as a means to recruit Union soldiers. Having accomplished his mission with the Union's victory, Douglass later celebrated his fallen friend through speeches delivered on multiple occasions, including one at Storer College in Harpers Ferry in 1881.

Douglass held a profound appreciation for Brown's enduring value to the cause of black freedom, consistently eulogizing him as a martyr and a classical hero. In the speech, he depicted the armory raid as a resounding thunderclap that ignited a morally deteriorating nation into action.Douglass emphatically proclaimed that Brown's defeat marked his true triumph, and his capture became the victory of his life.

Reflecting on his own ambivalence towards Brown's plans in 1859, Douglass acknowledged the remarkable power of his symbol following the execution, encapsulating the significance of the aged warrior. Douglass recognized Brown's unwavering commitment to his cause, emphasizing the transformative nature of his sacrifice. Brown's gallows took on a sacred significance comparable to the Christian cross, symbolizing his profound devotion and unyielding resolve.

In the wake of Brown's martyrdom, Douglass continued to honor his memory and the impact he had on the fight for black freedom.

Of John Brown, he said:

“With the Allegheny mountains for his pulpit, the country for his church and the whole civilized world for his audience…he was a thousand times more effective as a preacher than as a warrior.”

Despite his lack of skill in executing revolutionary violence, Brown managed to incite a broader revolution in America through his actions.

In the speech’s conclusion, Douglass declared:

"When John Brown stretched forth his arm, the sky was cleared. The time for compromises was gone, and to the armed hosts of freedom, standing above the chasm of a broken Union, was committed the decision of the sword. ... and thus made her own, and not John Brown's, the lost cause."

As a result, Douglass held Brown in eternal reverence as the hero of the abolitionist movement. During his speeches recruiting Black soldiers in 1863, Douglass would often burst into song, leading the crowd in "John Brown's Body," invoking Brown's spirit and inspiring young men to join the fight against slavery. Brown had evolved into more than just an adored figure; he embodied the very essence that kept the cause alive and propelled it forward during challenging times.

The impact of the events at Harpers Ferry had a transformative effect on the nation. It unleashed a tide of anger that traumatized Americans from all backgrounds. Southerners were gripped by fear of large-scale slave rebellions, while Northerners, who had hoped to postpone violent confrontations over slavery, were radicalized by the incident.

Prior to Harpers Ferry, political leaders believed that the growing divide between the North and South could eventually be resolved through compromise. However, after the events at Harpers Ferry, the divide seemed insurmountable. It fractured the Democratic Party, disrupted the Republican leadership, and created the conditions that propelled Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln to victory in the 1860 presidential election.

If John Brown's raid had not taken place, the 1860 election would likely have been a standard two-party contest between antislavery Republicans and pro-slavery Democrats. The Democrats would probably have emerged victorious, given that Lincoln received only 40 percent of the popular vote, around one million votes fewer than his three opponents.

The Democratic Party faced internal divisions over the issue of slavery, while Republican candidates like William Seward were tainted by their association with abolitionists. In contrast, Lincoln, seen as one of the more conservative options within his party at the time, benefited from the fragmentation of his opponents.

By disrupting the established party system, Brown inadvertently facilitated Lincoln's victory, which, in turn, led to the secession of 11 states and ultimately the Civil War. While Brown was initially dismissed as an irrational fanatic or worse, a more nuanced view has emerged with the civil rights movement and a deeper understanding of the nation's racial challenges.

Brown, though seen as hard and unconventional, possessed a profound empathy for the plight of of the enslaved. He defied the pervasive racism of his time and formed close friendships with Black Americans, often feeling more at ease in their company than with fellow whites.

Resources

https://www.biography.com/activists/john-brown-frederick-douglass-friendship

https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2020/06/hearing-frederick-douglass-his-speech-on-john-brown/

https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2011/spring/brown.html

https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3285

Books

Blight, David. Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018.

DeCaro, Louis A. John Brown: The Cost of Freedom. New York: International Publishers, 2007.

Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself. His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape from Bondage, And His Complete History to the Present Time. Octavo: Hartford, Conn., 1881.

DuBois, William Edward Burghardt. John Brown. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Company, 1909.

Reynolds, David S. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. Vintage, 2006.

Stauffer, John. The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race. Harvard University Press, 2004.