Monroe, North Carolina—–Robert Franklin Williams’ birthplace– was in 1925 like hundreds of other Southern communities was a rigidly segregated town, where all levels of white society and government were dedicated to preserving the racial status quo.

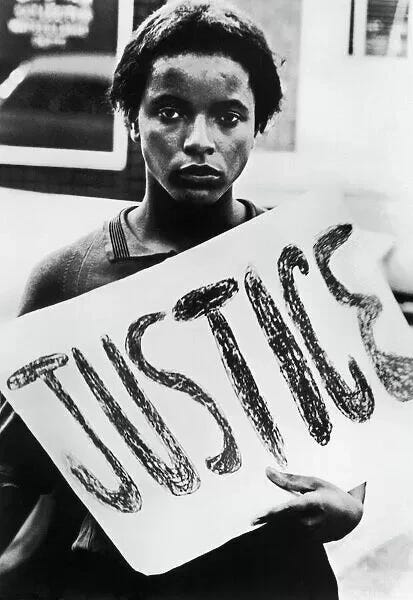

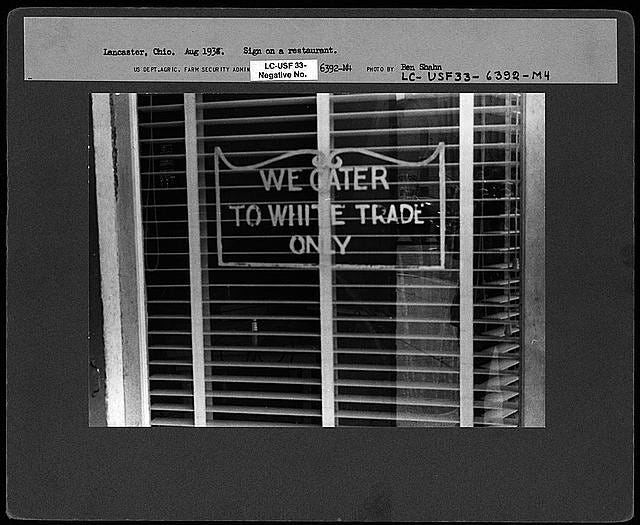

Black people lived under lynch law. “Whites Only” signs littered the town, including its library and swimming pool. And Black people who dared to speak out were subjected to brutal, sadistic violence. Indeed, it was common practice for convoys of Ku Klux Klan members to drive through black neighborhoods in Monroe County shooting in all directions.

The local white aristocracy–including the Helms family–ran the town. Old Man Helms was sheriff of Union County, whose seat is Monroe. His son, Jesse, became the Ku Klux Klan senator from North Carolina. Helms and the other local racist ruling families kept Monroe “safe” for Duke Power and the tobacco companies that really ran North Carolina.

And for the Southern Railroad–now the Norfolk Southern Company–controlled by the J.P. Morgan banking house in New York. Keeping Monroe “safe” meant keeping Black people down and keeping unions out. North Carolina still ranks lowest among the states in the percentage of unionized workers.

In Monroe, young Robert grew up listening to stories from his grandmother, Ellen, a former slave, and tales of his grandfather, Sikes, an advocate for the Republican Party who traveled throughout North Carolina during the Reconstruction era and ran a newspaper called The People's Voice. Before her passing, Ellen Williams entrusted young Robert with the rifle his grandfather had used to defend against white supremacy terrorists at the turn of the century.

Early on, Williams encountered racism firsthand. At the age of 11 in 1936, he witnessed a white police officer named Jesse Helms, Sr. brutally assault a Black woman, leaving her sprawled on the ground. Williams watched in horror as the father of North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms dragged the woman to a nearby jail, exposing her by lifting her dress, reminiscent of a primal act of capturing prey.

During World War II, Williams ventured to the North in search of employment. He participated in the Detroit Riot of 1943, a violent event where mobs of white individuals killed numerous black citizens. In 1944, Robert was drafted and served for 18 months in a segregated Army, fighting for freedom. Upon returning to Monroe, he married Mabel Robinson in 1947, as she shared his dedication to social justice and Black-American empowerment.

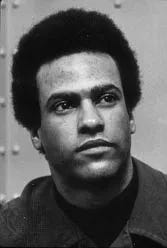

After he returned to Monroe in the late 1950s, Williams became active for the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

In Monroe—-the regional headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan—-Williams witnessed his community was denied fundamental rights, subjected to harassment by the Ku Klux Klan, and marginalized within the judicial system.

By 1955 the NAACP chapter in Monroe had dwindled down to six members. Williams, who had worked as a machinist in New Jersey and did a hitch in the Marines, took over its leadership.

He started a membership drive among workers and the unemployed. On too many Saturday nights, KKKers would drive through the Black community, shooting it up.

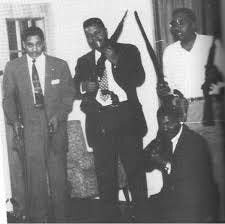

Many of these Klansmen came from South Carolina, whose border was only 14 miles away. When North Carolina Gov. Luther Hodges did nothing to stop the attacks, Williams and the local NAACP chapter formed a National Rifle Association chapter and trained its members in using firearms.

After enduring the situation for awhile,, Williams became radicalized. Faced with limited options, he began advocating for "armed self-reliance" as a means of combating white terrorism. Members of his NAACP chapter fortified their homes with sandbags and armed themselves with rifles to protect against Klan aggression.

Using military-surplus rifles from behind sandbag fortifications, the small band of freedom fighters drove off the larger force of Klansmen with no casualties reported on either side. It appears that the organized armed blacks of Monroe never shot any of their tormentors. The simple existence of guns in the hands of men who were willing to use them prevented greater violence.’

In the summer of 1957 a Klan motorcade attacked the home of NAACP member Dr. Albert E. Perry. An armed defense squad drove them off. Klan night riding came to a sudden stop in Monroe. This famous incident–which electrified so many Black people–was completely suppressed in the big-business media. Only Black publications such as Jet Magazine, the Afro-American and the Norfolk Journal and Guide reported the event.

Another case involved two young black boys, a seven-year-old and a nine-year-old, who were found guilty of rape and sentenced to indefinite terms in reform school after having been kissed by a white girl. On October 28, 1958, a mob of white men in Monroe, stormed the home of a nine-year-old Black boy named James “Hanover” Thompson , threatening to lynch him and David “Fuzzy” Simpson, seven years old after a white girl told her parents that she kissed them on the cheek when they were playing together earlier that day.

Earlier in the day, a group of children including James and David were playing together outside when they started a “kissing game,” during which a white girl their age named Sissy kissed James on the cheek. After the girl mentioned the kiss to her parents, her father grabbed a shotgun and arranged a mob to go to the Thompsons’ home, where they threatened to lynch James, David, and their mothers.

The boys were not home when the mob arrived but the police found them shortly thereafter and “jumped out with their guns drawn” before taking them into custody, where they were beaten by the police. James and David, unaware of why they were in custody, remained in jail for six days without being allowed to speak to their parents or any attorneys.

On October 31, a group of police officers broke into the boys’ cell wearing white sheets to intimidate them, while white residents of Monroe burned a cross on the Thompsons’ lawn and fired shots into their home throughout the boys’ detention. Both Evelyn Thompson and Jennie Simpson, the mothers of the two boys, were fired from their jobs.

After a brief hearing on November 4 in which they were denied the right to an attorney, James and David were charged with molestation and sentenced to “indefinite terms” at the state reformatory in Hoffman, North Carolina.

These two children–who could have been given the death penalty–were sentenced to 14 years in the reformatory. Only after Williams fought on and protests occurred throughout Europe did the state release the two.

Williams began a campaign urging officials to send the boys back to their families and wrote a letter on November 13 to President Eisenhower, who ultimately did not intervene. Finally, on February 13, 1959, over three months after James and David were sentenced to the reformatory, North Carolina’s Governor pardoned the boys and released them to go home. Neither the governor nor the court admitted to any wrongdoing, and no officials ever apologized to the boys or their families.

Several other cases of legal racism convinced Williams that Black -Americans could not get justice under the then system, and that armed self-defense was a necessity for black people. His organisation of armed squads of black people to fight off attacks by the KKK and his militant views had a large impact in black communities all over the country, especially because they proved effective.

“The Afro-American is a “militant” because he defends himself. His family, his home, and his dignity. He does not introduce violence into a racist social system – the violence is already there, and has always been there. It is precisely this unchallenged violence that allows a racist social system to perpetrate itself,” Williams wrote in his 1962 book Negroes With Guns.

Williams, often dubbed by the press as the “violent crusader,” intended his philosophy of armed self-defense to work in tandem with non-violent resistance. Instead, that philosophy became the catalyst for a national showdown between two opposing philosophies of the civil rights movement—-non-violence and armed self-defense.

Williams challenged not only white supremacists but also Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights establishment. He and his wife, Mabel, published the radical civil rights paper “The Crusader.” Williams was a counterpoint to the non-violent philosophy practiced by Martin Luther King. However he viewed it as self-defense.

“When the Klan is shooting at you,” he said, “you are justified in shooting back.”

As a result of this philosophy, the national NAACP suspended Williams for six months. Nonetheless, the Monroe NAACP chapter became famous for its militancy and for advocating self-defense against racist attacks.

North Carolina authorities were determined to get rid of Williams. They offered him bribes. When that didn’t work, they tried to kill him. In fact, on June 23, 1961, a racist thug named Bynum Griffin, the owner of a local car dealership, tried to run Williams off the road.

Operating with the complexity of the law, the Klan was unrelenting.

On Aug. 27, 1961, a full-scale assault was launched upon Monroe’s Black community. Freedom Riders came to Monroe, North Carolina to prove that passive resistance rather than armed self-defense would defeat the local Klan and improve race relations.

But on August 27th all hell broke loose.

An armed gang of racist thugs launched a brutal assault on Williams' neighborhood, driven by their hatred for his leadership role in the NAACP. They falsely accused Williams of actively inviting the Freedom Riders to Monroe. In truth, Williams had conflicted views about the Freedom Riders, seeing them as well-intentioned but naive youngsters who disastrously ill-prepared to confront the hardcore, died-in-the-wool violent racists who dominated Monroe County.

But they messed with the wrong one that day. A true believer in armed self defensea mob of armed KuKluxers attacked the Monroe NC neighborhood of NAACP leader, Robert F. Williams. But they messed with the wrong one that day. A true believer in armed self defense, Williams & his followers engaged in an intense shootout that sent the Klan bolting. , Williams & his followers engaged in an intense shootout that sent the Klan bolting.

Racists in law enforcement assaulted and jailed Freedom Riders-— demonstrators who had come from the North to overturn segregation.

By the end of the day, Freedom Riders had been bloodied, beaten, and jailed—-and Rob Williams was on the run from the FBI.

During this assault, the Stegalls, a white couple known for their Klan sympathies, drove through the Black community. Only Williams’ personal intervention prevented any violence against them. Yet, this action then became the basis of a phony kidnapping charge that was used to hound Williams out of the country. This charge was also used to jail one of Williams’ closest supporters, Mae Mallory.

“In thirty minutes you’ll be hanging in the courthouse square.”

So spoke A. A. Mauney, the Monroe, N.C., police chief, to Williams on Aug. 27, 1961. Williams–the president of the local NAACP chapter–wasn’t lynched that day. He was hounded into exile by the FBI.

Williams escaped the FBI dragnet and went to Cuba, where with the assistance of the Cuban revolutionary government he started the anti-racist “Radio Free Dixie.” Later, Williams would live in China, where he urged Mao Zedong to issue his famous message of support to African Americans.

Robert Williams remained a controversial figure for the rest of his life. He built strong relationships with world leaders like Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and Mao Zedong, and organized international support for the human rights struggles of African-Americans.

Huey P. Newton–the founder of the Black Panther Party–wrote how Williams’ book “Negroes With Guns” influenced him. Malcolm X had this to say: ‘Robert Williams was just a couple years ahead of his time.'”

Williams had a keen insight into the mind and character of the violent southern racists. In his book, Negros, with guns, he wrote:

“When an oppressed people show a willingness to defend themselves, the enemy, who is a moral weakling and coward is more willing to grant concessions and work for a respectable compromise. Psychologically, moreover, racists consider themselves superior beings and they are not willing to exchange their superior lives for our inferior ones. They are most vicious and violent when they can practice violence with impunity. This we have shown in Monroe.”

Williams also said:

“Nonviolence is a very potent weapon when the opponent is civilized, but nonviolence is no repellent for a sadist...Nowhere in the annals of history does the record show a people delivered from bondage by patience alone.”

Robert Williams wrote two books on his experiences growing up in the south and the racial tensions of the era: Negroes with Guns in 1962, the story of a southern black community's struggle to arm itself in self-defense against racists violent white supremacists.

In 1996, he completed, “While God Lay Sleeping: The Autobiography of Robert F. Williams,” a memoir of his lifetime experiences fighting for self-respect and dignity. It remains unpublished. Robert Franklin Williams died Oct. 15, that same year in Grand Rapids, Mich., at age 71. His story is a remarkable chapter in the history of Black liberation.

Historians have customarily portrayed the civil rights movement as a nonviolent call on America’s conscience–and the subsequent rise of Black Power as a violent repudiation of the civil rights dream.

But Williams reveals that both movements grew out of the same soil, confronted the same predicaments, and reflected the same quest for African American freedom.

Robert F. Williams was one of the most influential black activists of the generation that toppled Jim Crow and forever altered the arc of American history.

Contrary to the prevailing narrative that they were hapless victims of violence, Black Americans regularly handled business protecting themselves from the KKK & other racists.

As Robert Williams’s story demonstrates, independent black political action, black cultural pride, and armed self-reliance operated in the South in tension and in tandem with legal efforts and nonviolent protest.

Resources

https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/oct/28

https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai3/protest/text6/williamsnegroeswithguns.pdf

https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/robert-f-williams-black-power-north-carolina

https://www.ncpedia.org/listening-to-history/williams-mabel

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/williams-robert-f-1925-1996/

https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/robert-f-williams-black-power-north-carolina

Books

Williams, Robert F. "THE BLACK SCHOLAR INTERVIEWS: ROBERT F. WILLIAMS." The Black Scholar 1, no. 7 (1970): 2-14. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41163455.

Williams, Robert F. Negroes with Guns, (Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing, 1962).

Tyson, Timothy, ed. “Part 2: The Robert F. Williams Papers,” Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor. http://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/academic/upa_cis/9353_BlackPowerMove...

Barksdale, Marcellus C. "Robert F. Williams and the Indigenous Civil Rights Movement in Monroe, North Carolina, 1961." The Journal of Negro History 69, no. 2 (1984): 73-89. Accessed April 16, 2020. doi:10.2307/271759

Rucker, Walter. "Crusader In Exile: Robert F. Williams and the International Struggle for Black Freedom in America." The Black Scholar 36, no. 2/3 (2006): 19-34. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41069202.

Sturgis, Sue. “Remembering Southern Black freedom fighter Mabel Williams.” Facing South: A Voice for a Changing South. Institute for Southern Studies. April 25, 2014. https://www.facingsouth.org/2014/04/remembering-southern-black-freedom-f...

Tyson, Timothy. Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams & the Roots of Black Power (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

PBS; Independent Lens. "Negros with Guns: Robert F. Williams and Black Power."

Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance in the Civil Rights Movement (2004) by Lance Hill

The Making of Black revolutionaries (1997) by James Forman

Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power(2001) by Timothy B. Tyson