The Story of the Black Loyalists, Pt. 2

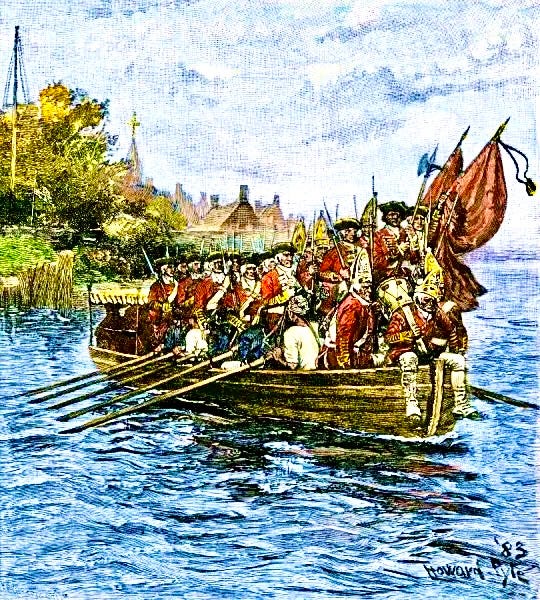

Image: Last boatload of British troops evacuating New York City, 1783. Hand-colored woodcut of a 19th-century Howard Pyle illustration.

The streets of British-occupied New York teemed with fear by the winter of 1782. Soldiers in red, refugees in rags, and the dispossessed of a revolution clung to the frostbitten edges of empire. In cellar corners and attic garrets, Black Loyalists—many of them formerly enslaved—listened for word of ships, of names entered in books, of freedom measured in the ink of British officials and the strength of a general’s promise. But what they heard instead was rumor, and what they felt was dread.

It was known, then, that the British would leave. The war was all but lost, and the American colonies would no longer be colonies. For white Loyalists—those who had pledged to the Crown and were now branded traitors—the prospect of exile was bitter but survivable. For Black Loyalists, it was far more than exile. It was escape—or it was re-enslavement.

Some had fought in British regiments, bearing arms in scarlet coats, drilling on cold ground under the vague promise of liberty. They had come not because they were loyal to a distant king but because the enemy of their enemy had become their only chance at freedom.

Others had labored in kitchens, foraged for food, or served in sabotage. But all of them, whether soldier or servant, had read the same signs in the faces of their former masters: that the defeat of Britain meant the return of “property.” Old masters came North. Men from Georgia, from Virginia, from the Carolinas—tramping into New York with legal papers and old whips, claiming bodies like cargo. These men had not come not with armies to fight. They had come to reclaim.

Image: An illustration of Black Loyalist Richard Pierpoint.(artwork by Malcolm Jones, courtesy Canadian War Museum.

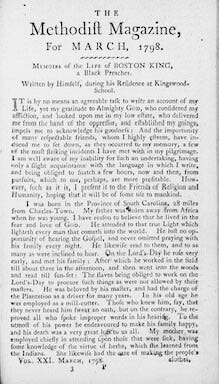

In the press of crowded streets, Black men disappeared. In the alleys near the docks, they were seized. Boston King, once enslaved, remembered the terror of that winter: friends who had walked with him just days earlier now dragged away by the wrists, eyes wide with disbelief. Some were taken by their former owners. Others, perhaps most cruelly, were taken by opportunists who had never owned them, but saw in dark skin a chance for profit. In the chaos, truth mattered less than assertion. The city, King wrote, was no longer a refuge. It was a hunting ground.

The Treaty of Paris, the document that ended the war, seemed to seal their fate. No Negroes were to be carried away, it said—an agreement meant to soothe southern rage and ensure white property was restored. But in those cold and crumbling barracks, the Black Loyalists knew that if they were not “carried away,” they would be buried in chains. For a time, even the British hesitated. The Empire’s word was on trial.

And then came Sir Guy Carleton.

As commander of the British forces in New York, Carleton made a choice that would reverberate through history. He would not return the Black Loyalists. They had earned their freedom, he told Washington. They were not property. They were free at the time of the treaty—and so they would remain. It was a defiant act, and a dangerous one.

Image: General Sir Guy Carleton, by unknown, ca. 1923. Courtesy Library and Archives of Canada.

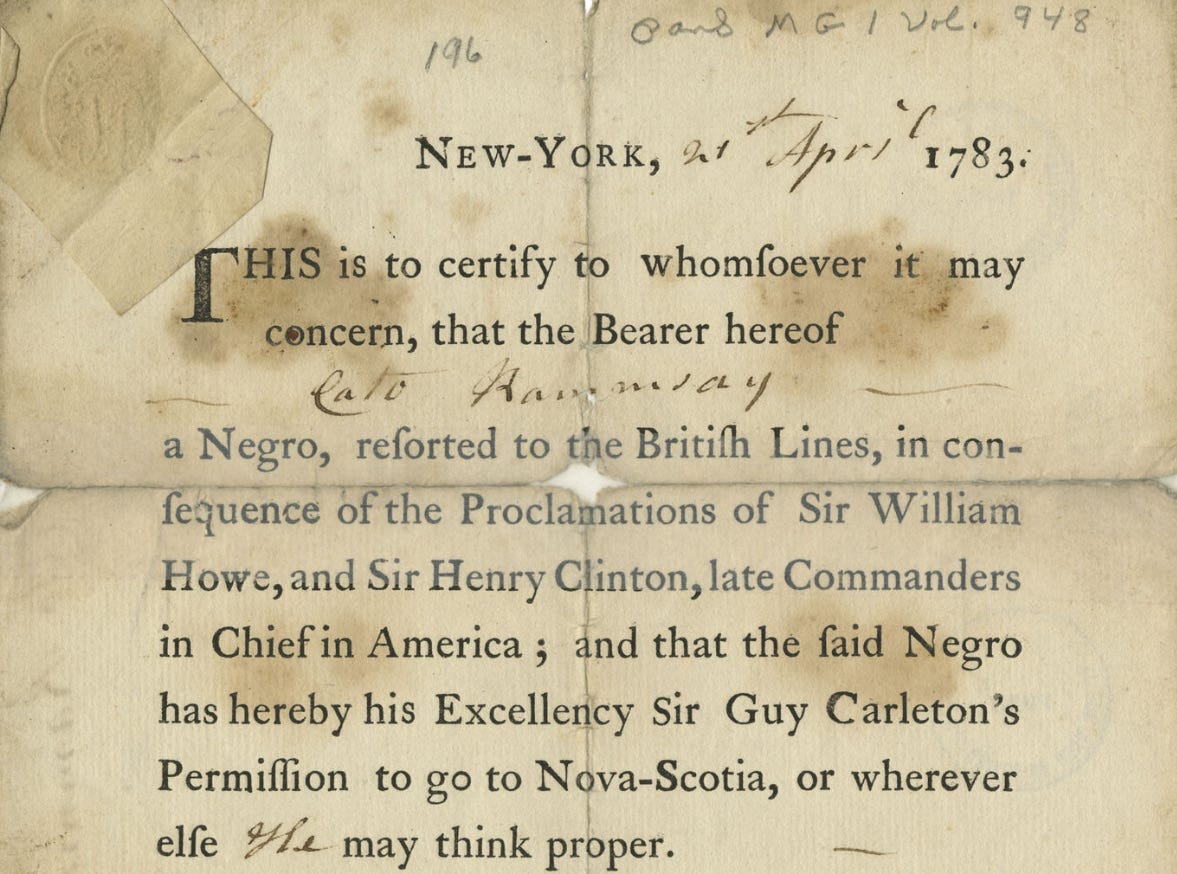

To enforce this claim, Carleton commissioned the Book of Negroes, a ledger that would record the names, ages, histories, and services of those Blacks who would leave with the British. Brigadier General Samuel Birch issued Certificates of Freedom, each one a fragile shield against the grasping hands of those who saw liberty as theft. A commission reviewed claims, but justice was uneven: of fourteen contested cases, most were decided for the slaveholders. Even in freedom, the weight of property law pressed against their bodies.

By the summer of 1783, the docks of New York became the threshold between two worlds. Ship after ship set sail for Halifax, for Port Roseway, for Birchtown. On board were Black men and women who had gambled everything—who had run from plantation fields to British lines, fought in foreign uniforms, and placed their fate in a crown across the sea. In their hands they held certificates, scraps of proof that freedom had been promised. In their hearts, perhaps, they held something less certain.

For not all would make it.

Image. Boston King, “Memoirs of the Life of Boston King, a Black Preacher. Written by Himself, during his Residence at Kingswood-School,” Methodist Magazine, March-June 1798.

In Charleston, where the British lost their grip before protections were secured, the evacuation turned savage. Anarchy reigned. Thousands of Blacks were taken—some counted as slaves, some as free, many in the blurred middle. In the South, as in war, ambiguity was a weapon. Without Carleton or Birch, without books or certificates, Black Loyalists were once again what others claimed they were.

Some, like Mary Postell, were taken before they could board. Others made it, only to be enslaved again by men who wore the king’s colors and the planter’s smile—Loyalists like Jesse Gray and Joseph Robin, who made their livings off Black freedom. In Shelburne, in courtrooms flying British flags, the law often sided not with the freed, but with the one who claimed owners

Elsewhere, ships from Florida left behind their Black passengers when Spain reclaimed the colony. The Spanish had no allegiance to British promises. Freedom was not a passport they recognized. They sailed not for London, but for Nova Scotia. For Birchtown. For Port Roseway. For a land colder, rockier, harsher than any they had known. They carried people who had been born into chains and had broken them—not with war, but with the decision to flee into war. They left with nothing but names on paper, and the promise that those names would be enough.

Image: Passport for Cato Ramsay to emigrate to Nova Scotia, Date: 21 April 1783, Nova Scotia Archives.

But in Nova Scotia, on cold Atlantic shores, small communities formed. Birchtown. Digby. Preston. Places where liberty, though threadbare and tested, took root in the soil. They arrived in clothes that barely held together.

They came to Nova Scotia not because it was paradise but because it was not the plantation. They came with nothing, built from nothing, and found—again—that freedom was not a destination but a daily struggle.

They built with axes and prayer. And though hunger and cold would claim many, they were there. And they were free. And that, to a Black Loyalist in 1783, was everything.

Primary Sources

Book of Negroes (Carleton Papers)

Library and Archives Canada. Carleton Papers – Book of Negroes, 1783. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/loyalists/book-of-negroes/Pages/introduction.aspx.

Boston King, Memoir

King, Boston. “Memoirs of the Life of Boston King, a Black Preacher. Written by Himself, during His Residence at Kingswood School.” The Methodist Magazine, March–June 1798. Reprinted by the Black Loyalist Heritage Society. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/king-memoirs.htm.

Nova Scotia Archives – Book of Negroes Ledger

Nova Scotia Archives. The Book of Negroes, 1783. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/archives/?ID=26.

Passport for Cato Ramsay

Nova Scotia Archives. “Passport for Cato Ramsay to Emigrate to Nova Scotia.” April 21, 1783. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/archives/?ID=39.

Secondary Sources

Walker, James W. St. G. The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Whitfield, Harvey Amani. North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016.

Hill, Lawrence. The Book of Negroes. Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 2011. (Note: historical fiction based on archival records, not a primary source but often cited in public discourse.)

The Canadian Encyclopedia. “Black Loyalists in British North America.” Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-loyalists-in-british-north-america.

BlackPast.org. “Black Loyalists Exodus to Nova Scotia (1783).” Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/black-loyalists-exodus-nova-scotia-1783/.

Holton, Woody. Liberty Is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Pybus, Cassandra. Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty. Boston: Beacon Press, 2007.

White, Michael Anthony. 2019. Liberty to Slaves: The Black Loyalist Controversy. Master’s thesis, University of Maine.

Websites

https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/king-memoirs.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Once again,so much I didn't know.

I did, of course know about Carleton's book and his refusal to Washington to return the slaves.

But that was two lines of history.

With your PhD., are you now teaching I would lie beneath your lectern seeking your knowledge.