The Story of the Black Loyalists, Pt. 5 (Conclusion, Pt. 1 of 2)

Image: of the water from Birchtown. Photo by Bonnie Huskins. Source: https://acadiensis.wordpress.com/2019/12/02/bonnie-huskins-reviews-stephen-davidsons-birchtown-and-the-black-loyalist-experience-from-1775-to-the-present/

The Land They Were Given

They were promised land. That was the word—land, not money, not houses, not provisions or safety. Land. Land enough to start over. And so, when the Black Loyalists came ashore in 1783—after the war, after New York, after the lists had been drawn and names entered in British ledgers—they looked at the sweep of the harbor and waited to be told where their piece of the promise would lie.

It lay to the north and east of Shelburne, in a place later called Birchtown, on the far arm of the harbor. To reach it, they had to pass the rocky ridges near the water and descend toward the interior, where the forest closed in thicker, the roots tighter, the trees taller and less forgiving. What they saw was not what they had imagined. The ground was not open; it was not level; it was not rich. There were no fields here, no river-bottom meadows, no stone-free pastureland. There were stones—stones everywhere, crowding the thin soil, pressing up from beneath with every frost. And there was swamp—dark, standing water in the hollows just beyond the birches, reeds and cattails climbing where fields were meant to be.

They had come, many of them, from the Tidewater, from Carolina, from the Georgian coast, from the red-soiled fields of the Chesapeake—places where land spread flat and wide and warm. In those lands, even in slavery, they had learned to read the earth. But this land spoke a different tongue. Its winters howled through the seams of crude huts, and its forests seemed to grow back the moment they were cut. The men who had marched with shovels in the Black Pioneers now hacked with dull axes at trees that bent the wrong way, splintered unevenly, cracked rather than fell.

Image: Slavery was developed in Virginia so planters could acquire a cheap labor force to grow tobacco. Source: Library of Congress, Tyler, His Family and His Allegiance to the South

The white settlers of Port Roseway had some advantage: many had come from Massachusetts or Rhode Island. They knew what a northern winter was, what it required of a man, of a roof, of a wall sealed tight. But the Black Loyalists did not. The cabins they knew were built for heat, not cold. The homes they could build—if they could build them—were made of what the land would give them. And the land gave little.

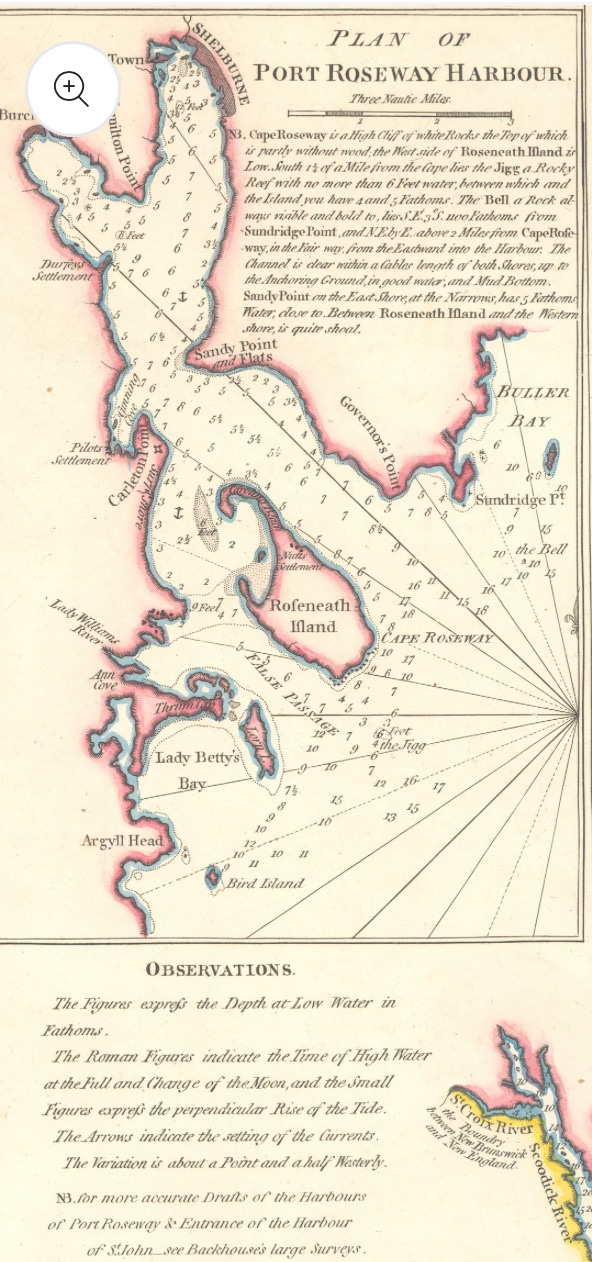

Even in summer, the earth in Birchtown was reluctant. It was acidic, pebbled, shallow. The roots of trees tangled close to the surface and made planting difficult. Streams ran through it, but not cleanly—more seep than flow, more bog than brook. And the harbor—beautiful to the eye, a gleam of silver between the pines—was unkind to work. Its waters were shallow, hemmed in by jagged rock; even small boats had trouble navigating its length. It was not a place from which to trade, nor a place from which to sail. It was a cul-de-sac of empire.

And yet that was where they were sent.

Farmland, if it could be called that, stretched only a few yards from the water’s edge before giving way to glacial stone. Birch and spruce and alder covered what was left. And behind that, the swamp. The swamp crept forward slowly, swallowing paths, undermining corners of huts, turning low ground to black mire. And when the rains came, as they always did in Nova Scotia’s coastal months, they did not soak in. They sat. Pools lingered for weeks. Disease followed.

In winter, the land changed character again. The wet turned to frost, then to deep ice. The air sharpened. Winds rolled in off the Atlantic and sheared through the forest canopy and into every poorly chinked wall. Fires were kept burning day and night, not for comfort but survival. Smoke hung low in the huts, stung the eyes, blackened rafters made from sapling poles.

And when help came—when lumber was brought from Shelburne, when tools were shipped in from Halifax—the white settlers took it first. The Black settlers, who had cleared most of the land by then, building roads, cutting timber, hauling stone, received the scraps. Or nothing at all.

Image: A Pit House. Photo by Bonnie Huskins. Source: https://acadiensis.wordpress.com/2019/12/02/bonnie-huskins-reviews-stephen-davidsons-birchtown-and-the-black-loyalist-experience-from-1775-to-the-present/

They built anyway.

They dug trench shelters and lined them with branches. They gathered birch bark and wove it into shingles. They used mud for mortar and rock for foundation, though the rock was cold and the mud never held. They lived in these huts, some no larger than ten feet across, for years. And when they heard, in 1786, that a magistrate had torn down a “Negro hut” in Shelburne because it was being used for dances, they must have known exactly what that meant. Their community was not a town. It was a boundary. A margin.

There were forests on every side of Birchtown, but those forests belonged to someone else. There was farmland nearby, but it had already been granted away. And when the white settlers hired a private surveyor to take the western shore, one-third of Birchtown was carved out and claimed—gone. Behind them, the swamp. In front of them, land that had been spoken for. What was left was rock.

But still they stayed.

Because the rock was theirs. Because the promise, though broken, had not been entirely withdrawn. And because in that land, in that soil, however poor, they could at least be free.

The Land Beyond Birchtown

If Birchtown was hemmed in by rock and swamp, the other Black settlements in Nova Scotia were shaped—defined, constrained, hardened—by the land in different ways. They were scattered across the province, flung to its peripheries, to its interior reaches and poorest soils, places a government could assign without cost and forget without guilt.

Tracadie was one such place. It lay far to the northeast, on the margins of Guysborough County, deep inland where rivers bent narrow and the wind from the Atlantic no longer reached. The men and women who settled there had not chosen it; they had been moved. First to Port Mouton, which burned. Then to Guysborough, which stalled. Then, in 1786, they were sent to Tracadie. The grant was 3,000 acres, but it was land granted for a reason. It was thin soil, rock-littered, choked with spruce and fir, the kind of land that could not be coaxed to yield—not easily, not quickly, and not without tools most of the settlers did not have.

Image: The Roseway River, Nova Scotia. Near Birchtown Bay. Source: https://www.alltrails.com/canada

There were forests, yes. But not the kind that invited clearing. The ground beneath was uneven, roots coiled over stone. And the stone itself—granite, slate, glacial till—lay near the surface in great gray slabs. Streams crossed the land, but they were dark, cold, narrow, and sometimes still. Water pooled more often than it flowed. Farming here was not impossible. But it was hard. And the hardest part was not the work—it was the waiting.

Because even after being granted the land, the Black Loyalists of Tracadie could not work it—not officially—not until the lots were surveyed. And the surveyor did not come. He had stopped being paid. And so, for years, the people of Tracadie lived not on granted land, but beside it, adjacent to a promise. By 1799, most had abandoned their claims. The land remained, but it belonged to others. The names on the deeds changed. The stones in the ground did not..

Image: Detailed inset map of Burch Town (Birchtown) and the black suburb of Shelburne. Published London 12 July 1798, Cartographer: Captain Holland, Nova Scotia Archives.

In Brindley Town, the story was similar. It had begun as hope—a cluster of families placed near a growing town on the Fundy coast. The land, at first, seemed better. The air was saltier, the wind faster, the soil looser than in Tracadie. But it was claimed. Church land. And when the settlers tried to stay, they were told to move. So they did. Again. And again. And each move meant rebuilding—huts, gardens, paths—each one costing time, labor, hope.

The surveyor here, too, stopped working. He had not been paid. The settlers, with nothing to spare, had to reach into empty pockets to pay him themselves. Without a deed, even poor land was not truly theirs. And what they could build was always provisional, temporary, vulnerable to removal.

Preston, by contrast, had location. It was closer to Halifax, on the northeast side of Dartmouth, near the markets. And that meant opportunity—of a kind. Fifty families were settled there in 1785, given 40-acre lots. But the land, like so much of what was given, was poor. It was sandy in some places, acidic in others. It had once been forest, and the stumps were still there, stubborn, spreading like ribs through the clearing. What it had going for it was not fertility, but access.

It was near Halifax. And Halifax needed labor.

So Preston became something different—a place of work, not of farming. A place where men walked miles to sell what little they could grow or to take jobs unloading ships, digging ditches, laying stone. And because they were near the city, near the seat of government, white landowners watched. They saw a chance. Some had been granted more land than they could clear—if it remained uncleared, they might lose it. The solution was simple. Hire a Black family. Let them clear it. Let them plant it. And when the title was secure, take it back.

It was called sharecropping. But it was not shared.

Lacking tools and farm animals, black farmers had to clear land with their bare hands. Source: https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/story/suffering/stones.htm

And so the land itself shaped lives—not just by what it gave, but by what it withheld. In Tracadie, it withheld access. In Digby, it withheld permanence. In Preston, it withheld ownership. In all three, it made the word “freedom” ring differently. Not false—but conditional. Always provisional. Always, like the land itself, in need of clearing.

Still, they remained. They cleared the brush. They drained the swamp. They pried roots from stone with hands that had once hauled cannon for the British. They worked with what they had. And when the soil refused them, they moved on, or endured, or rebuilt again.

What they were building was not just homes. It was a claim—not yet legal, not always visible, but rooted in earth and sweat and frost.

And over time, it held.

Primary Sources

British Government. Book of Negroes. 1783. Nova Scotia Archives. Accessed May 28, 2025.

https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/book-of-negroes/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3070438?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Clarkson, John. The Clarkson Papers. Edited by Kenneth C. Barnes. London: Hakluyt Society, 1998.

https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/diaries/mission/153-155.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://equianosworld.org/associates-abolition.php?id=9&utm_source=chatgpt.com

Colonial Office Records. Nova Scotia Correspondence and Land Grants. CO 217. The National Archives (UK).

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C4408

Shelburne Muster Rolls and Blucke Papers. 1783–1791. Nova Scotia Archives and Shelburne County Museum Collections.

https://loyalist.lib.unb.ca/record/local-records-1782-1860

Fergusson, Charles Bruce, ed. Clarkson's Mission to America, 1791-1792. Publication No. 11. Halifax: Public Archives of Nova Scotia, 1971.

https://archives.novascotia.ca/african-heritage/archives/?ID=686

Hodges, Graham Russell, ed. The Black Loyalist Directory: African Americans in Exile after the American Revolution. New York: Garland for the New England Historical Genealogy Society, 1995.

https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/6919744

MacNutt, W. S. Select Loyalist Memorials: The Appeals for Compensation for Losses and Sacrifices to the British Parliamentary Commission of 1783 to 1789 from Loyalist of the American Revolution who came to Canada. Typescript. University of New Brunswick Archives and Special Collections. See

https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/americanloyalists.pdf

Stephen Blucke’s Leadership in Birchtown.

https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/people/secular/blucke.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Secondary Sources

Barry Cahill, “The Black Loyalist Myth in Atlantic Canada”, Acadiensis, XXIX, 1, (Autumn 1999),pp.76-87.

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/download/10801/11588/14683

Schama, Simon. Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution. New York: HarperCollins, 2006.

Walker, James W. St. G. The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993.

Whitfield, Harvey Amani. “Black Loyalists and Black Slaves in Maritime Canada.” Acadiensis (2012).

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/acadiensis/article/view/20066/23079

Whitfield, Harvey Amani. North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016.

Winks, Robin W. The Blacks in Canada: A History. 2nd ed. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000. See

https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/SCMicroR5858.pdf

Further Reading