In 1887, a young seaman embarked on a new chapter of his life as a shop clerk for a furrier in Washington, D.C. Though his days as a sailor were behind him, his spirit of wanderlust and longing for adventure remained strong. It was during this time that a serendipitous moment unfolded, forever altering the course of his destiny. A naval officer entered the shop, bringing with him a collection of precious seal and walrus pelts freshly acquired from an expedition to Greenland.

Intrigued by the young man's evident passion for exploration and worldly experiences, the officer was quick to recognize his potential. Impressed by his previous seafaring background, the officer wasted no time in offering him a remarkable opportunity. The young man was hired as the officer's personal assistant, and was extended an invitation to join the officer on his next assignment—an invitation that would set in motion a thrilling journey of discovery and forge a decades long bond between the two adventurers. This fateful encounter marked the beginning of a partnership that would see them conquer the harshest of terrains and leave an indelible mark on the annals of history.

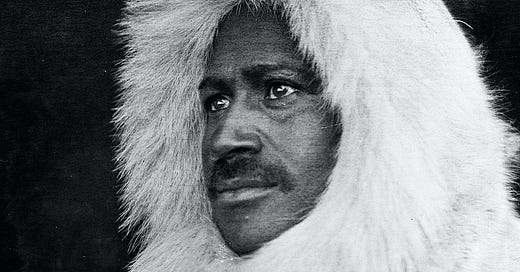

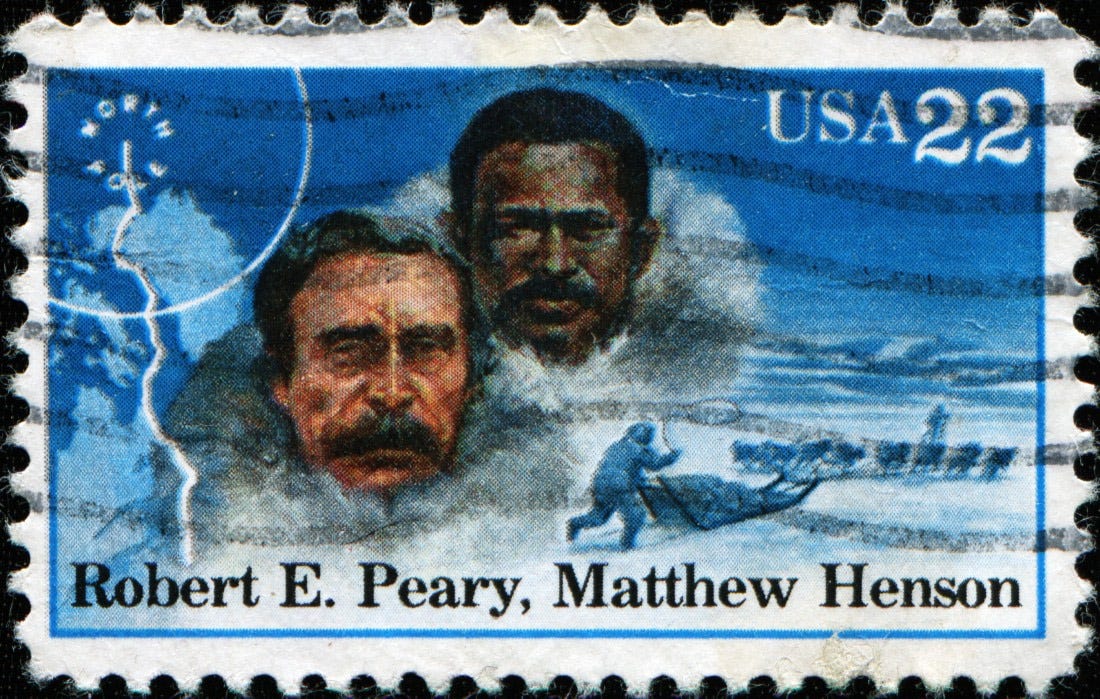

So occurred the first meeting of Matthew Henson and Robert Peary.

An Inauspicious beginning

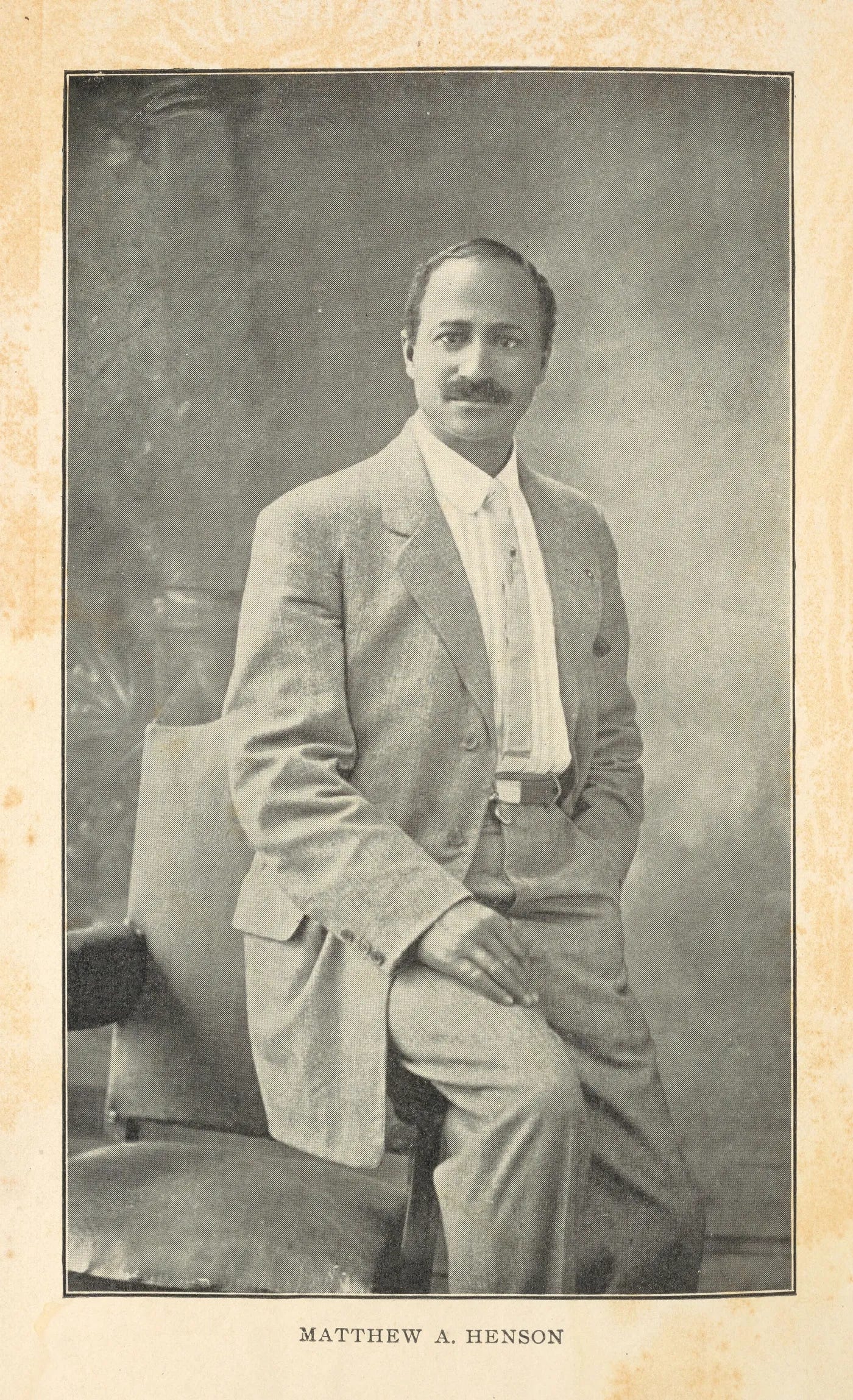

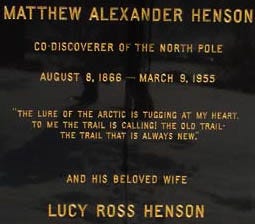

Born one year after the Civil War, in Charles County, Maryland, Matthew Alexander Henson, was about as far away from the adventuring life as young boy could get—-a child of a sharecropping family—-a common occupation for Black Americans in that era. The farm on which the family tilled was located near the Potomac River, approximately 40 miles south of Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, this is about the extent of the limited information available about his early years that can be independently confirmed. According to Henson’s account in A Negro Explorer at the North Pole: The Autobiography of Matthew Henson, his parents, Lemuel Henson and his second wife Caroline, relocated to Washington, D.C. when he was a young child. Henson's mother passed away when he was only seven, and he was subsequently raised by an uncle.

However, an alternative narrative of Henson's childhood can be found in other sources, including Dark Companion, a biography penned by Bradley Robinson in collaboration with Henson himself. According to Robinson and other accounts, Henson's mother passed away two years after his birth, and his father, who had remarried, died when Henson was eight years old. Living with his stepmother, whom he described as unkind, Henson took matters into his own hands and ran away from home at the age of 11. Seeking refuge in the vicinity of Washington, D.C., he found employment as a kitchen assistant in a small cafe where he encountered Baltimore Jack, a sailor who frequented the establishment. It was through Jack's captivating stories of maritime adventures that Henson's fascination with the sea grew, eventually leading him to embark on his own nautical journey. Driven by his fascination with tales of the sea, the 12-year-old embarked on a new journey as a cabin boy on a merchant ship, the vessel, Katie Hines. During his six years onboard, Henson not only honed his sailing skills but also took the opportunity to educate himself, learning to read, write, and navigate.

When he met Robert Peary at the DC hat shop, Peary was preparing for a surveying expedition in Nicaragua. Peary discovered Henson's extensive experience in sailing and navigation. Recognizing the young boy’s talents, “The Commander,” as Henson in his writings referred to Peary, offered him a position as his valet. Henson joined Peary on the Nicaragua expedition in 1888, impressing him with his skills and determination. This successful collaboration led to their partnership on seven Arctic expeditions from 1891 to 1909.

Contested Accomplishment

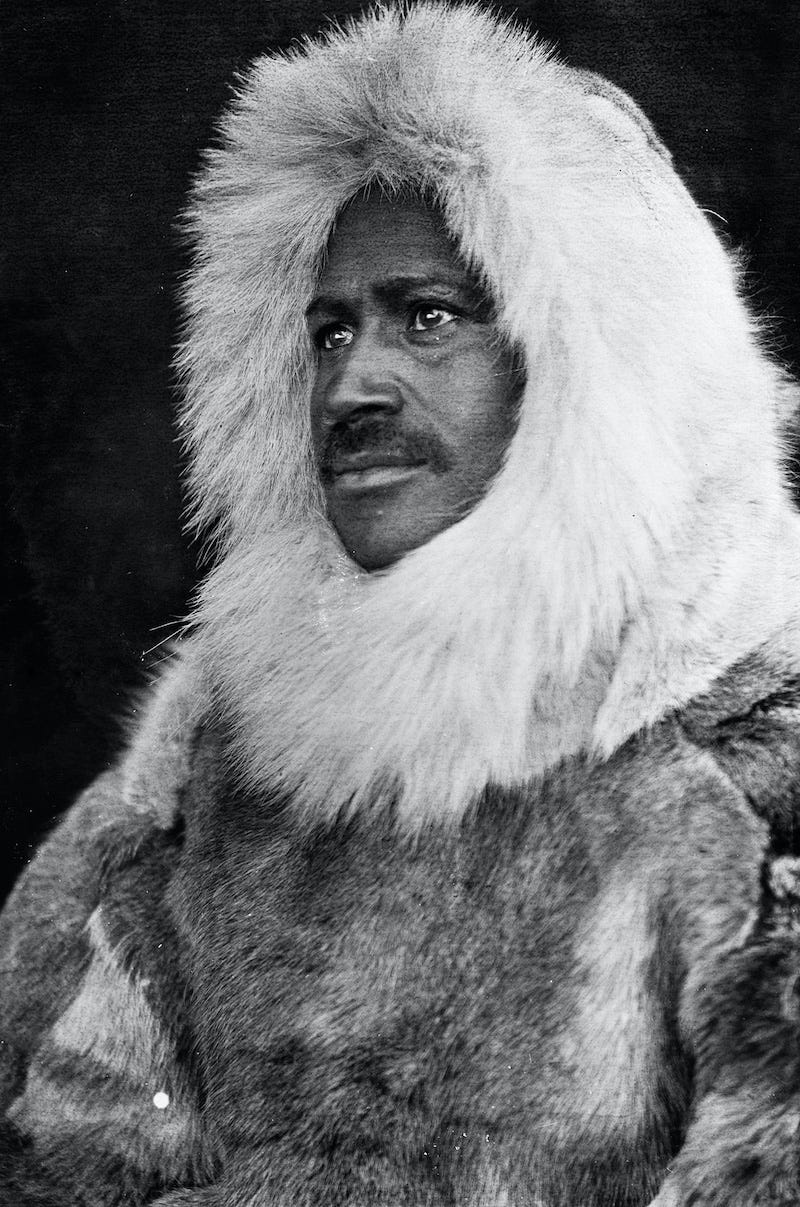

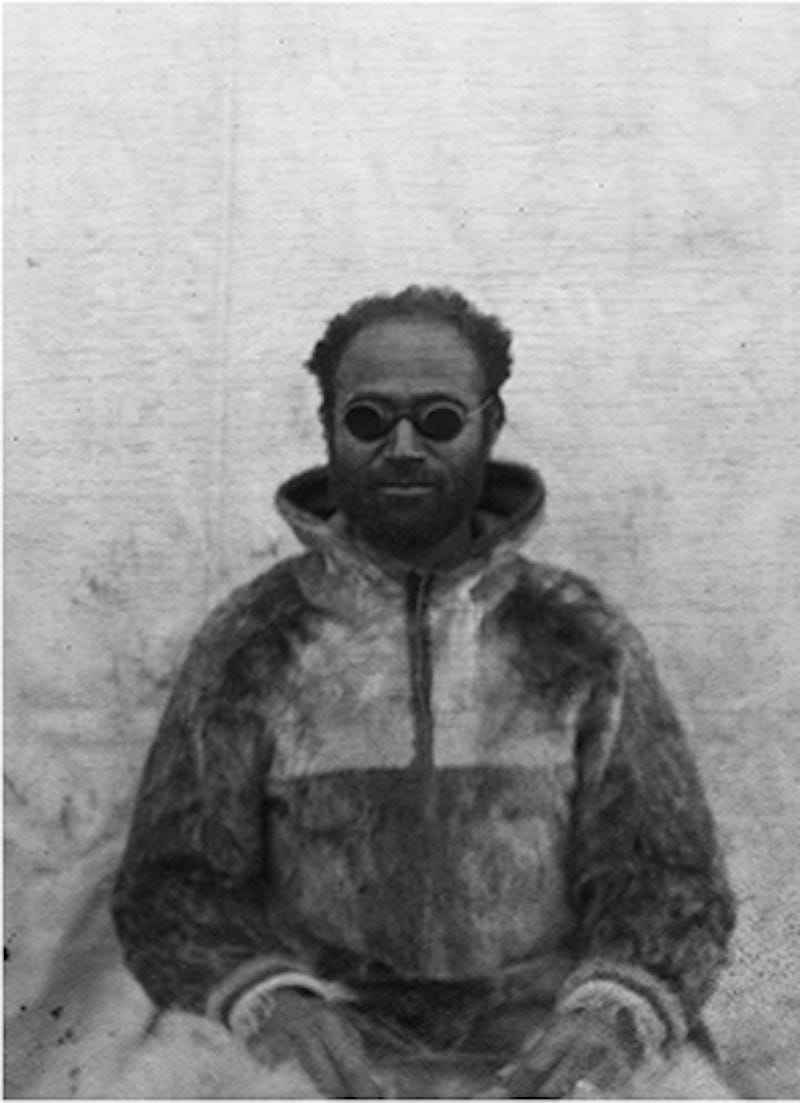

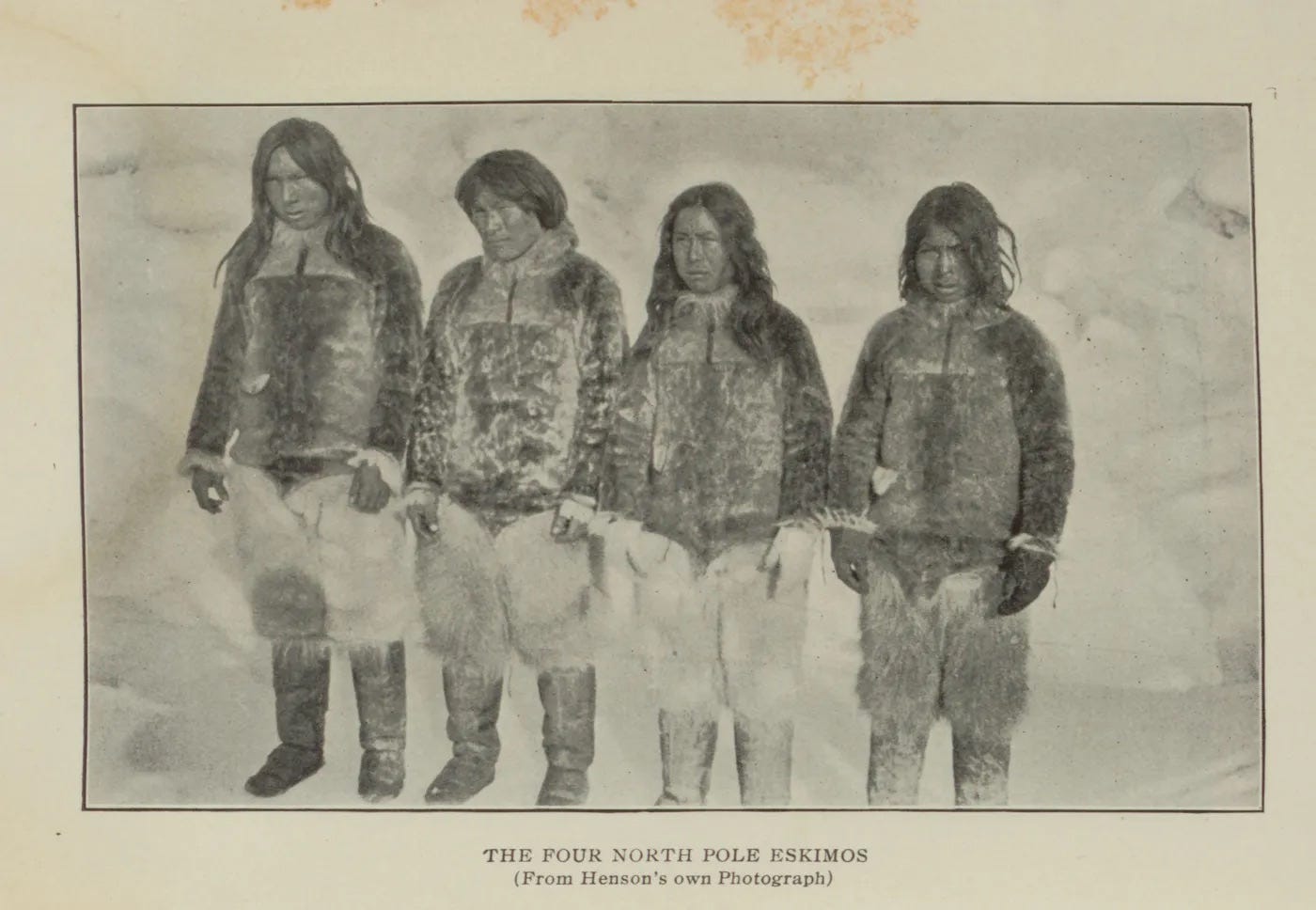

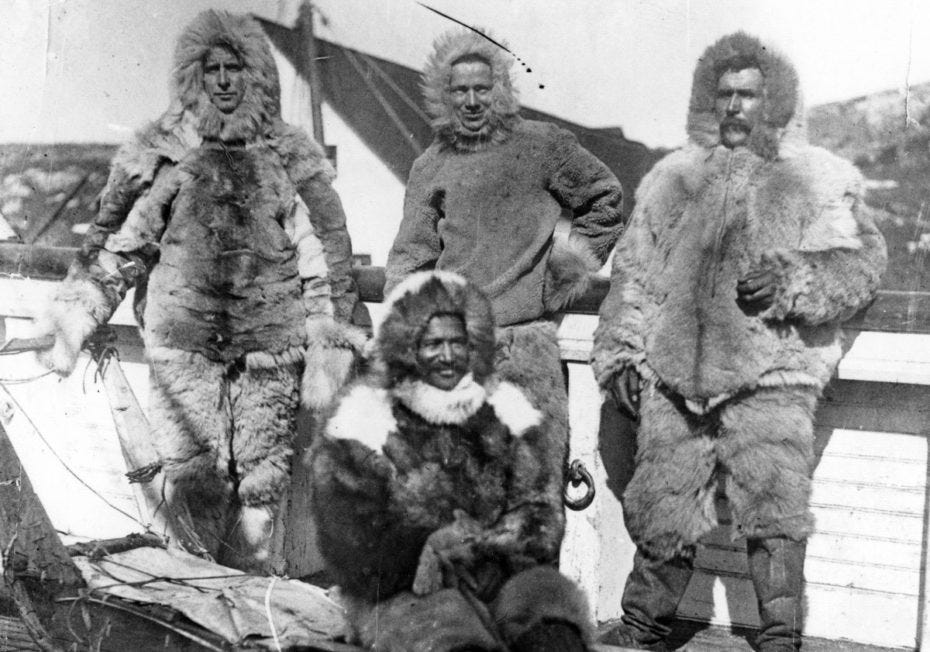

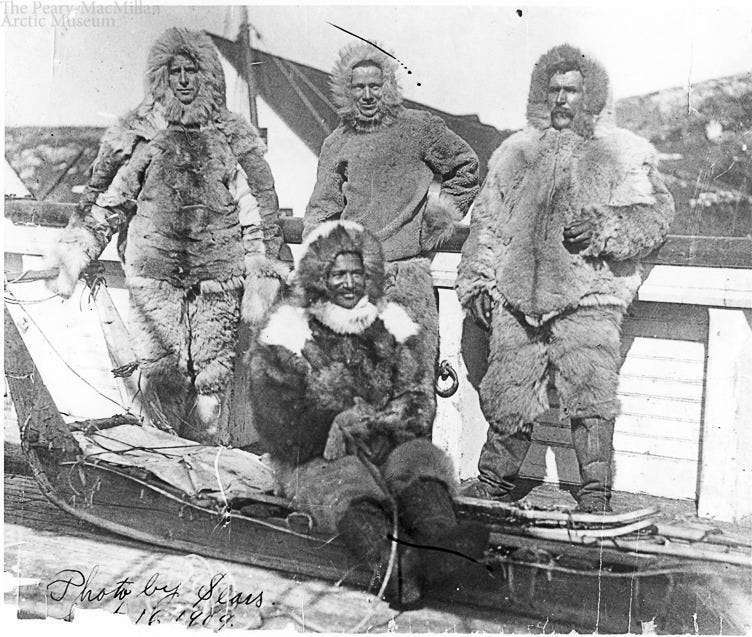

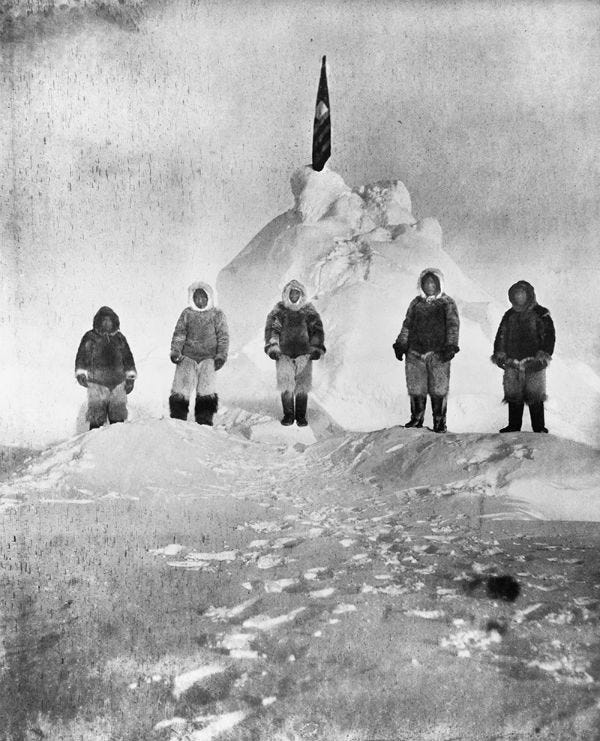

On April 6, 1909, Henson, along with Peary and four Inuit assistants finally accomplished the historic feat of setting foot on the North Pole. Henson always insisted that he was the true first among the group to reach the North Pole, challenging Peary's assertion.

Henson recounted his experience on the day of discovery:

"The results of the first observation showed that we had accurately determined the distance, as the flag hoisted over the geographical center of the Earth was positioned just behind our igloos."

The raised flag signified group’s successful arrival at the North Pole. However, the question of who reached the pole first remained unresolved. In a newspaper article after their return, Henson admitted,

"I was leading but overshot the mark by a few miles. We retraced our steps, and I could clearly see that my footprints were the first at the spot."

Upon returning to the United States, reports in the press suggested tension between Peary and Henson regarding who deserved credit for reaching the North Pole first. Henson later, shared his heartbreak, stating:

"From the moment we confirmed our arrival at the Pole, Commander Peary hardly spoke to me. It deeply saddened me that he would rise in the morning and silently leave for the homeward trail, without rapping on the ice for me, which was the established custom theory.”

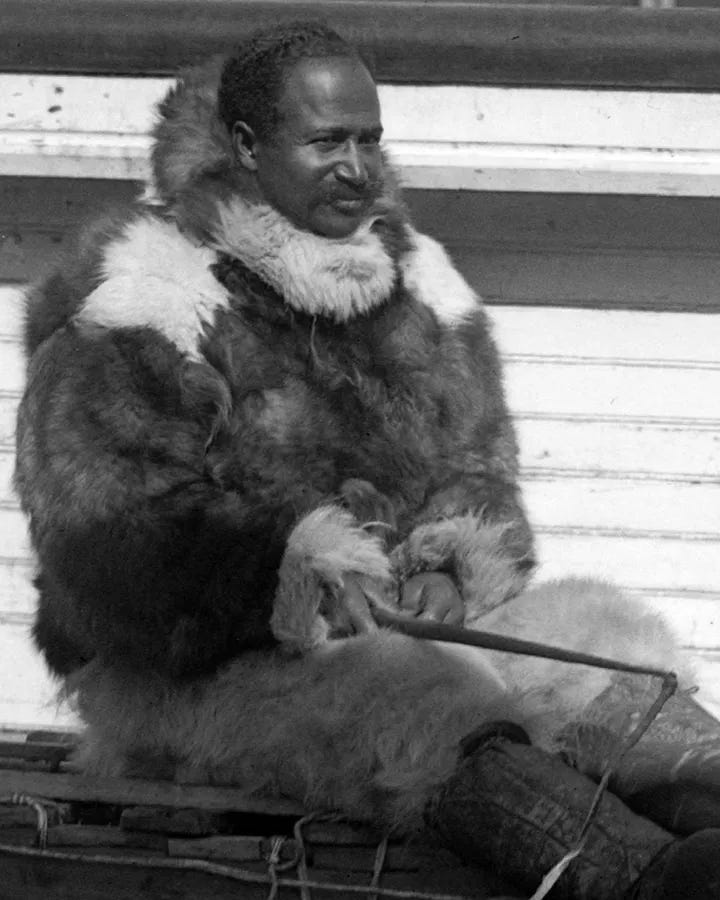

The debate surrounding their achievements adds complexity to the narrative, but Henson's story is significant in recognizing the contributions of African Americans to society. Unlike Peary, who hailed from a lineage of imperial White explorers that often disregarded the welfare and culture of native peoples, Henson held a profound respect for Inuit culture. He was warmly regarded by the Inuit, who affectionately called him "Mahri-Pahlu," meaning Matthew The Kind One.

Henson possessed exceptional skills and knowledge that greatly contributed to the success of their journey to the North Pole. With extensive experience living and working in Arctic regions, Henson accompanied Peary on multiple expeditions prior to their final attempt. He acquired survival techniques from the Inuit, such as building igloos, navigating using landmarks and stars, and enduring extreme cold weather.

Henson's expertise in dog sledding and his ability to interact with Inuit communities along the way proved invaluable. Moreover, Henson's remarkable physical endurance and resilience allowed him to withstand the harsh conditions they encountered during their trek. These distinctive skills and attributes set Henson apart and played a pivotal role in their mission to reach the North Pole.

Their relationship, however, became strained after the expedition. Peary was unwilling to share his polar honors, even if disputed, and rejected the idea of sharing the achievement with fellow explorer Bob Bartlett, his second-in-command. Peary's decision was motivated by racist assumptions, as he believed that a Black man like Henson would not be seen as eligible to share such accolades.

Despite Henson's crucial role in the final march to the North Pole, the "long and close friendship" between him and Peary faded upon their return. In the following decade, Peary made no effort to maintain their friendship, never inviting Henson to his home and showing minimal support or recognition for his contributions. Henson only learned of Peary's death through a newspaper article.

In 1912, Henson published A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, providing an account of his experiences. However, compared to Peary, he received relatively little immediate recognition for his part in the 1909 expedition. Henson spent the remainder of his career in relative obscurity, working as a clerk at the U.S. Customs House in New York City.

It was not until later in his life, more than three decades after their partnership ended, that Henson finally received the well-deserved recognition. In 1937, he became the first African American to be made a lifetime member of The Explorers Club, an elite organization. In 1944, Henson was awarded the Peary Polar Expedition Medal, and he was received by Presidents Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower at the White House.

In 1988, after his death, Henson and his wife, Lucy Ross Henson, were reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. The remains were buried near the gravesite of Admiral Peary and his wife, Josephine Deibitsch Peary. This symbolic gesture marked the culmination of national recognition that Henson had long deserved. In the same year, the National Geographic Society posthumously awarded Henson the prestigious Hubbard Medal, the highest honor bestowed by the society.

Despite the challenges and the lack of acknowledgment during his lifetime, Henson's legacy continues to be celebrated. In 2000, he was honored with the Hubbard Medal by the National Geographic Society. And in September 2021, the International Astronomical Union named a lunar crater after him, further solidifying his place in history.

The story of Matthew Henson illuminates remarkable achievements and exposes prevalent prejudices and injustices. His determination, expertise, and invaluable contributions to Arctic exploration challenge the narrative of polar expeditions and highlight the vital role African Americans played in shaping our world.

Today, Henson's legacy inspires with the power of perseverance and resilience. His story prompts recognition and honor for overlooked African American contributions throughout history. Henson's indomitable spirit and pioneering efforts continue to inspire, reminding us that greatness transcends race and background.

In celebrating Henson's life, we not only acknowledge his personal triumphs but also honor countless unsung heroes who made significant contributions to human progress against all odds. Their stories, like Henson's, deserve to be heard and cherished, shaping our understanding of the past and inspiring a more inclusive and equitable future.

Resources

All images from National Geographic Society

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/the-legacy-of-arctic-explorer-matthew-henson

https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/explore/notable-graves/explorers/matthew-henson

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-discovered-the-north-pole-116633746/

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20230418-matthew-henson-the-us-unsung-black-explorer

https://www.popularmechanics.com/adventure/outdoors/a22500/peary-henson-cook-race-north-pole/