The Montgomery Bus Boycott is a model for collective solidarity and positive representation in the service of movement objectives. It did not receive as much attention as the March on Washington or even Bloody Sunday but the press’ coverage of the boycott received a fair amount of positive coverage. Portrayed as a spontaneous act of dissension, rather than the carefully planned event and continuous effort it was in reality, the Montgomery Bus Boycott exemplified the complex issue of Black solidarity and moral authority in the face of violence and intimidation. Throughout American history, Black Americans enforced racial loyalty as a constructive social norm in order to police its members’ behavior. This policing of racial boundaries and acceptability continues to the modern era. For example, African Americans’ response to the 2008 Professor Cornell West versus Barack Obama debate was mostly unexplored by mainstream media and dismissed as an internal "black issue."

Collective coercion has largely gone unnoticed in the mainstream White press. Indeed, over the years, only a few elite magazines and newspapers have attempted to unpack the role of Black solidarity as a vital element in promoting collective legal interest and effecting public policy.

During the Montgomery Bus Boycott, some Black Americans felt differently about not taking the buses because it was a hardship—-long hours of walking, bartering rides, hostile reception from White employers. Not everyone wanted to be an activist! However, as a means of racial coercion, other Black Americans labeled these errant members Uncle Toms and traitors to the race because the dissenters’ actions violated the established racial norm of black suffrage. This kind of rough treatment signaled to any others who were thinking of rebelling to conform or face similar harsh treatment. Altogether, swift retribution toward those deemed "traitors to the race" stemmed from the effects of breaking solidarity with the broader community, and was not necessarily aimed at personal retribution against the betrayer.

The tactic of shaming errant members as “sellouts,” “race traitors,” “house negros,” “tools of the man,” and worse was learned through the hard experience of life in bondage. Many a plot for freedom was undermined by treachery and that experience helped Black Americans understand the value of racial policing and how such norms could be constructed, disseminated, applied, and enforced. Of course, the branding of those who disagree as race traitors could be used in destructive ways too. Over-regulating speech and expression can discourage creativity and innovation—-crucial to communities solving complex social problems.

So it was that during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, social coercion was used to penalize those who consciously promoted the objectives of anti-African-American interests or who lacked due concern for "the race." As the author, Brando Simeo Starkey notes on African-American community loyalty:

“By marshaling support for certain goals, solidarity provided African-Americans with a path toward legal gains. By itself, it is inadequate. But in concert with other tools such as strategy, moral authority, organization, etc., black solidarity was invaluable. The Montgomery bus boycott, the 1960s student movements, and project confrontation in Birmingham in 1963 exemplify black solidarity, in tandem with other tools, that help produce civil rights victories. Even when substantive legal remedies never eventuated, solidarity nonetheless provided a starting point from which to resist subordination.”

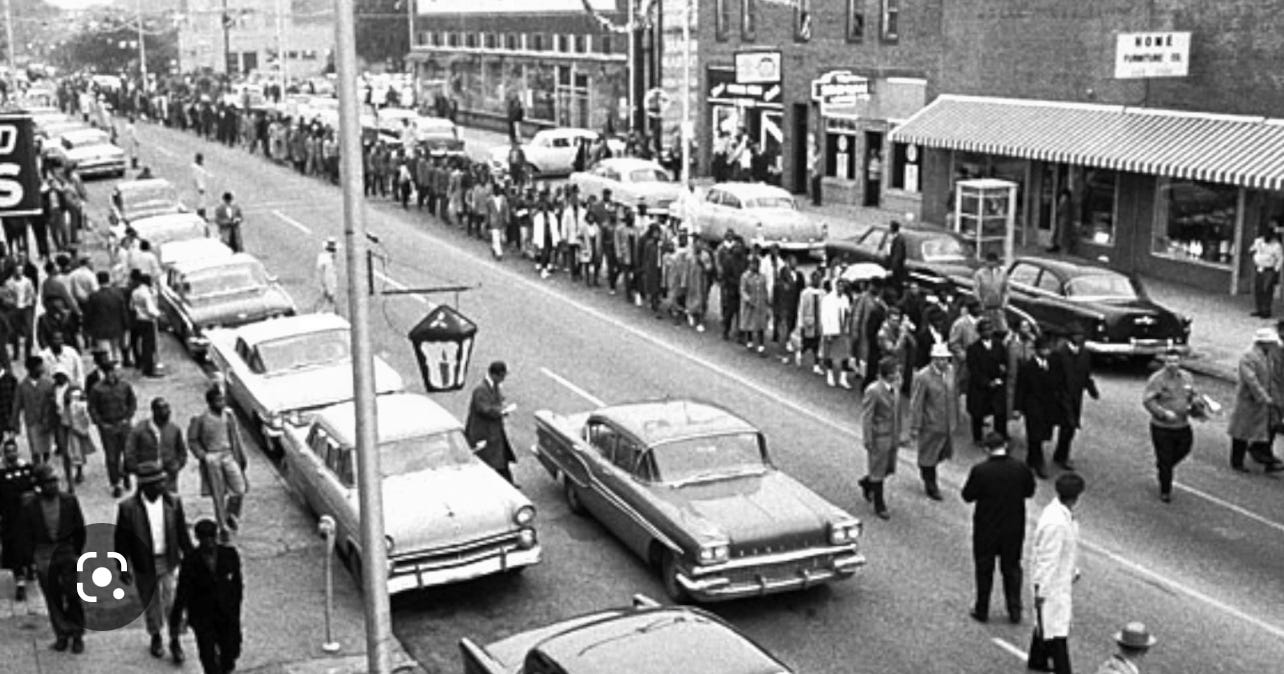

Properly establishing social norms and, when necessary, social coercion, helped galvanize the Montgomery community and beyond. Indeed, it was in Montgomery where Martin Luther King Jr.’s arrest and trial received national coverage. In Montgomery, King's application of the Gandhian principles of nonviolence toward the cause of bringing down southern segregation, reached a much larger audience than it would have had movement organizers been undermined by dissent. Broadcast worldwide, news media images of hundreds of well-dressed, dignified, hard working Black citizens, marching stoically to work directed an intense gaze on what was happening to Southern United States. And it was a major embarrassment for Southern authorities because it undermined the stereotypes Whites had promulgated so frequently of Blacks as troublemakers and attention seekers. This press coverage resulted in a well of support from individuals and organizations outside of Montgomery (even internationally).

King’s December 20, 1956 statement on ending the boycott offered quiet testimony to the power and effectiveness of collective solidarity:

“For more than twelve months now, we, the Negro citizens of Montgomery have been engaged in a non-violent protest against injustices and indignities experienced on city buses. We came to see that, in the long run, it is more honorable to walk in dignity than ride in humiliation. So in a quiet dignified manner, we decided to substitute tired feet for tired souls, and walk the streets of Montgomery until the sagging walls of injustice had been crushed by the battering rams of surging justice.”

Sources

Starkey, B. S. (2014). In Defense of Uncle Tom. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, D., & Greenhaw, W. (2006). The Thunder of Angels: The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the People who Broke the Back of Jim Crow. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books.