Image: Harold Dahmer, the 26-year-old son of Vernon Dahmer Sr., stands outside the family home after the Ku Klux Klan attack that killed his father on Jan. 10, 1966.

Vernon Dahmer's legacy in fighting for voter registration and against racial terror is emblematic of the grassroots activism that characterized the civil rights movement. His story serves as a poignant example of individual contribution to the collective struggle for justice and the ultimate price paid by those leading the fight. His story is a powerful narrative of resistance and resilience against the backdrop of one of America's most oppressive periods for race relations.

Image: Vernon Dahmer in his cotton field, September 1964

In Mississippi, at the heart of the civil rights movement’s most turbulent era, Vernon Dahmer was a stalwart figure in grassroots activism. His dedication to securing voter registration for Black Americans and his fierce opposition to racial violence placed him as a central character in the fight for justice. His life story encapsulates the singular contributions and sacrifices made by civil rights soldiers and offer a compelling story of defiance and endurance amidst severe racial strife in America.

Vernon Dahmer's life began on March 10, 1908, in the Kelly Settlement, Forrest County, Mississippi, into a family of African American farmers. His upbringing in the segregated South was during a time when Jim Crow laws were firmly in place, enforcing racial segregation and the disenfranchisement of African Americans.

Growing up, Dahmer was exposed to the harsh realities of racism and the value of hard work and self-reliance. His family's background in farming meant that from a young age, he was involved in the day-to-day operations of the farm, which instilled in him a strong work ethic. This early experience on the farm also likely nurtured his understanding of the importance of economic independence for Black Americans.

Dahmer’s parents, George and Ellen Dahmer, were part of a well-established middle-class black community in the Kelly Settlement. They owned a substantial amount of land, which was not common for Black Americans in Mississippi at the time. This relatively stable economic foundation allowed Vernon to pursue education through the 7th grade, after which he left school to help full-time on the family farm. His education was typical for black children of that era, who often received limited schooling due to economic pressures and racial discrimination.

Image: Ellie Dahmer, Vernon’s mother.

George Dahmer, Vernon’s father.

Young Vernon was of mixed race, with a light complexion that would have allowed him to pass for white. However, despite the potential privilege his white skin could have afforded him in a racially segregated society, Dahmer chose to live as a black man and to fight for the rights of African Americans. His decision to identify with the black community and work on its behalf was an important aspect of his character and his legacy.

In the Jim Crow South, the “one-drop rule” legally and socially classified individuals as black even if they had “one drop” of African ancestry, regardless of their physical appearance. Dahmer’s choice reflects the convictions of many mixed-race individuals during the era who, despite the potential for passing, opted to align themselves with the struggle for justice and equality within the black community. It also speaks to the complex nature of racial identity in the United States and the personal decisions it necessitated in the face of systemic racism and discrimination.

Image: Circuit Clerk Theron Lynd with voter registration applicants in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, January 22, 1964, Moncrief Photograph Collection, MDAH

Despite the pervasive racism of the time, Dahmer became a successful businessman, owning a store, sawmill, and a farm. He used his economic independence to advocate for the rights of Black Americans in Mississippi, taking a significant risk by publicly supporting voting rights when doing so was met with hostility and violence. Dahmer’s commitment to economic self-sufficiency and community empowerment was a cornerstone of his work, reflecting his belief that economic independence was crucial to civil rights advancement.

In the early 1960s, Black Americans in Mississippi faced significant barriers to voting, including literacy tests, poll taxes, and outright intimidation. Dahmer was deeply involved in efforts to dismantle these barriers. He believed that economic independence and the right to vote were interlinked tools for civil rights and consistently used his resources to support voter registration drives. Dahmer often paid the poll taxes for those who couldn't afford them, enabling more members of the Black community to vote. His store served as a haven for civil rights workers and a place where African Americans could freely discuss civil rights issues, including voting.

Image: Vernon Dahmer at his fish fry on July 4, 1964, Herbert Randall Freedom Summer Photographs, USM

Dahmer served as president of the Forrest County Chapter of the NAACP and led voter registration drives in the 1960s. He famously stated, “If you don’t vote, you don’t count,” which encapsulated his lifelong crusade for equality and the importance he placed on the right to vote as a tool for change. His leadership in the NAACP put him at great personal risk, yet he persisted in his advocacy, believing in the transformative power of enfranchisement.

Dahmer's leadership extended beyond voter registration. He was known for taking a public stand against injustices when such actions could result in deadly consequences. By the mid-1960s, Dahmer had become a target for white supremacists who sought to maintain segregation and prevent Black American political participation. Despite these threats, he used his voice on local radio stations to encourage voter registration, knowing the airwaves were one place where the message could be spread without interruption.

The Ku Klux Klan targeted Vernon Dahmer because of his work in support of civil rights for Black Americans, specifically his efforts to register black voters in Mississippi. Dahmer's active participation in the civil rights movement, his high-profile role in the NAACP, and his outspoken advocacy made him a marked man in the eyes of the Klan.

Samuel Holloway Bowers was the leader of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi, one of the most violent factions of the Klan during the 1960s. Bowers was deeply involved in the Ku Klux Klan's operations against the civil rights movement and was implicated in numerous acts of violence and intimidation against civil rights activists.

Bowers's animosity toward Vernon Dahmer stemmed from Dahmer's efforts to promote African American voting rights. Dahmer, as mentioned, openly defied the institutionalized racism of the era by encouraging black voter registration and by publicly stating that he would pay the poll tax for those who could not afford it. This defiance made Dahmer a target for the Klan's most extreme elements, who were committed to maintaining segregation and white supremacy by any means necessary.

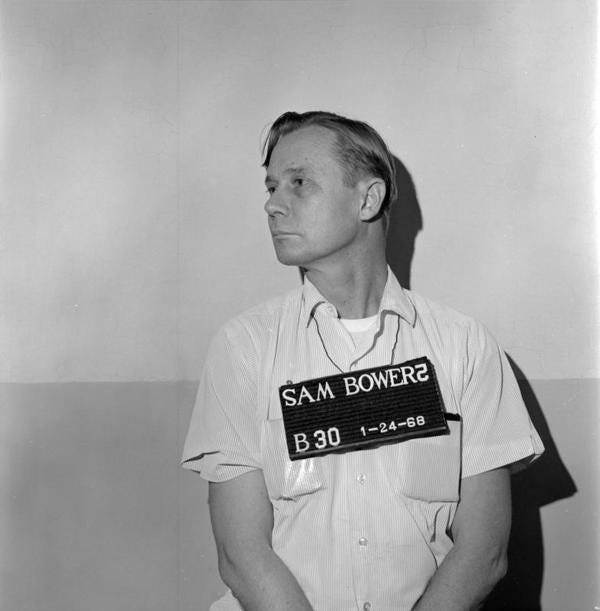

Image: January 24, 1968, arrest photos of Sam Bowers, who was arraigned in Forrest County Circuit Court (Hattiesburg, Miss.) on a charge of arson in the January 10, 1966, firebombing of Vernon Dahmer's house and store.

Members of the Klan were known to use fear and terror tactics to enforce their racist ideologies and suppress the African American vote, which they saw as a threat to white supremacy. While the exact statements made by the Klan about Dahmer specifically are not well documented in public records, their actions against him speak volumes about their sentiments. The Klan’s decision to attack and ultimately murder Dahmer was a violent assertion of their stance against racial equality and anyone who worked to advance the civil rights of black individuals.

The night after a radio broadcast where Dahmer reiterated his commitment to the voting rights cause, the Ku Klux Klan attacked, making him pay the ultimate price for his activism.

On the night of January 10, 1966, Bowers orchestrated a firebombing of Dahmer's home and store, leading over a dozen Klansmen in a pre-dawn surprise attack. They threw Molotov cocktails, igniting the property, and shot into the house to block the family's exit. In a display of remarkable bravery, Dahmer returned fire against the assailants, enabling his wife and children to escape. Throughout the ordeal, he shouted instructions to his family, even as he was being injured by the fire and inhaling smoke, ultimately suffering severe burns due to his valiant efforts to protect his loved ones.

Image: Vernon Dahmer, Sr. and his wife, Ellie. Source: WDAM.

After the assault, Dahmer was taken to a local hospital for treatment. Unfortunately, the extent of his injuries proved to be too severe, and he died on January 10, 1966, a little over a day after the attack. His death was directly due to the burns and the respiratory complications from smoke inhalation, which overwhelmed his body's ability to recover.

Vernon Dahmer’s family reported that on his deathbed, after the attack on his home by the Ku Klux Klan, he was concerned about the safety of his family and the well-being of others. His last words were reported as being focused on the well-being of his family rather than on himself, despite his serious injuries. It's said that he told his wife, “I've been shot, but I am not hurt badly. Take care of the children.” This exemplified his selflessness and dedication to both family and the larger cause of racial equality.

His last known public words, spoken over the radio the day before he was attacked, echoed his commitment to the civil rights cause: "If you don't vote, you don't count." These words captured his dedication to equality and voting rights.

Image: Vernon Dahmer funeral, Shady Grove Baptist Church, Kelly Settlement (Hattiesburg, Miss.), afternoon of January 15, 1966. Ellie Dahmer, widow of slain civil rights leader Vernon Dahmer, assisted to car by family members.

The attack highlighted the Klan and Sam Bowers's belief in using terror to counteract the civil rights movement. In Bowers's view, civil rights activists like Dahmer were enemies of the racial order he sought to protect, and extreme violence was a justified means of opposing them. Indeed, Dahmer's death highlighted the extreme risks faced by those who stood up against racial injustice during one of the most turbulent times in American history.

The attack left his wife and children without a husband and father, and it set off a wave of national outrage. The incident exposed the viciousness of the Klan's opposition to the civil rights movement and heightened awareness of the dangers faced by activists in the South.

Image: Vernon Darmer's widow, Ellie, holds his photograph, next to her son, Vernon Dahmer, Jr

The Klan wanted to terrorize the black population and prevent them from voting, but the attack on Dahmer did not crush the civil rights movement in Mississippi; it strengthened it instead. The brutality of the incident attracted national attention to the resistance against civil rights and spurred government protection for activists.

The killing of Vernon Dahmer had a significant impact beyond Mississippi. It contributed to increasing federal involvement in civil rights issues in the South and played a role in the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which sought to eliminate barriers to voting for African Americans. It also emphasized the urgent need for federal and state protections for civil rights workers against racially motivated violence.

The aftermath of Vernon’s murder saw a lengthy judicial process that spanned over three decades.It wasn't until 1998 that Bowers was convicted for ordering the firebombing and murder of Dahmer, as previous trials ended in mistrials, mainly due to white juries' reluctance to convict. Sam Bowers was eventually sentenced to life in prison, marking a belated measure of justice for the Dahmer family.

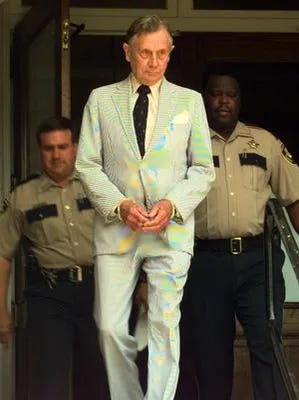

Image: On Aug. 21, 1998, KKK Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers is convicted of the 1966 murder of Vernon Dahmer for ordering the KKK's attack on the NAACP leader and his family.

The pursuit of justice for Dahmer’s murder also reaffirmed the determination of civil rights advocates to continue the struggle against racial oppression and violence. Bowers's conviction for the murder of Vernon Dahmer was a late but important step in acknowledging the brutal history of racial violence in the South and the lengths to which white supremacists would go to maintain racial inequality. Bowers's life and actions remain a stark example of the violent resistance to the civil rights movement and the systemic racism that activists like Dahmer worked tirelessly to overcome.

Following Vernon Dahmer's death, his family upheld his legacy with extraordinary fortitude. His widow, Ellie Dahmer, embodied the resistance against intimidation by continuing her husband's work within the community and taking a stand as an election commissioner. Her determination to participate in this civic role was a powerful act of defiance against the Klan's objective to inhibit the black vote.

Despite the severity of the Klan's violence, the Dahmer family's dedication to Vernon's vision remained unwavering. Ellie's role as an election commissioner in Forrest County was not just a personal achievement but a symbol of the ongoing struggle for civil rights and the relentless pursuit of justice and equality that Vernon Dahmer championed. Despite the tragedy that befell her family, she remained in Hattiesburg and worked tirelessly to continue her husband's work in advocating for civil rights and improving the lives of Black Americans.

The Dahmer children also maintained their father’s legacy of activism. The family's commitment to civil justice and their work within the community have kept Vernon Dahmer's memory alive and highlighted the ongoing struggle for racial equality in the United States.

The Dahmer family's efforts after Vernon’s death not only kept his memory and mission alive but also underscored the broader impact of the civil rights movement, showcasing the resilience and courage of those who fought — and continue to fight — against racial injustice in America. They stood as a testament to the belief that such work must be carried on across generations to ensure lasting change.

Vernon Dahmer's fight for voter registration and his stand against racial terror in Mississippi were central to his life's work and critical to the broader civil rights movement in the South. This brave man understood that real freedom for his people lay not only in the ability to vote and participate in democracy but also in economic independence and education. His leadership in voter registration efforts and his challenge to the disenfranchisement of black voters in Mississippi were directly influenced by his experiences and the lessons learned during his formative years in Forrest County.

Dahmer’s death sparked national outrage and led to an increased push for civil rights protections, reinforcing the resolve of civil rights activists nationwide. His legacy is a testament to the courage and leadership required to combat systemic racism and injustice. The establishment of the Vernon Dahmer Park in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, the scholarship funds in his name, and the election of his wife, Ellie J. Dahmer, to the local election commission, all reflect the enduring impact of his life’s work.

Dahmer’s commitment to equality and justice remains influential, reminding us that the fight for civil rights often demands great personal sacrifice. His story is taught in schools, commemorated by civil rights tours, and continues to inspire activists. In the history of Mississippi’s struggle for civil rights, Vernon Dahmer stands as a hero whose determination, sacrifice, and legacy continue to illuminate the path towards a more just and equal society.

Resources

https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-rights-era.html

https://www.loc.gov/item/2015669153/

https://www.digitalcollections.usm.edu

https://www.digitalcollections.usm.edu

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/features/dahmer.htm

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/civilrights/importantpeople.htm

Books

Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Armstrong, Thomas M. Autobiography of a Freedom Rider: My Life as a Foot Soldier for Civil Rights. Health Communications Inc, 2011.

Branch, Taylor. At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-68. Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989.

Branch, Taylor. Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-65. Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Bullard, Sara. Free At Last: A History of the Civil Rights Movement and Those Who Died in the Struggle. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Cobb Jr., Charles E. This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

Moody, Anne. Coming of Age in Mississippi: The Classic Autobiography of Growing Up Poor and Black in the Rural South. New York: Bantam Bell, 1966.

Payne, Charles M. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2007.

This is outstanding, thank you.