Image: Locd and Loaded by Denise Lee

In 1967, Black Panther leaders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were pulled over by Oakland police, their vehicle loaded with weapons.

When asked about the firearms, Newton put his legal knowledge on full display by stating that he was only obligated to provide "identification, name, and address."

On the police's instruction, he exited the vehicle, rifle in hand, and declined to justify why he and Seale were armed. As a crowd assembled, Newton welcomed them, aware that under California law, bystanders could lawfully observe an arrest without interfering.

Without any legitimate reason to detain the Black Panthers and with an increasing number of witnesses, the police had no choice but to let them go.

This encounter empowered the Panthers. They began monitoring police activities, offering legal guidance to Black Americans confronted by the police while lawfully armed.

It was the beginning of what the Panthers would call their "police patrols."

Image: Molly, get your gun! Woodcut from Molly Gutridge, A new touch on the times: (Danvers, MA: Ezekiel Russell, 1779.

The origins of gun control in the United States of America date back to the foundational years of the nation. When the first European settlers arrived on American shores, they brought with them not just hopes of a new beginning, but also their perceptions of power and control.

As colonies formed, so too did laws—laws that often sought to ensure the dominance of European settlers over indigenous populations and slaves. In the years of the American colonies, relations between European settlers and Native Americans were fraught with tension, often stemming from land disputes and cultural misunderstandings.

As settlers sought to safeguard their newly claimed territories and fortify their positions, they instituted laws that restricted or outright prohibited Native Americans from possessing firearms.

This was a strategic move, designed to limit the potential threat posed by indigenous populations who might resist encroachment upon their ancestral lands.

Meanwhile, as the transatlantic slave trade blossomed and the plantation economy of the South grew reliant on the labor of enslaved Africans, there emerged a palpable fear among white slaveholders of Black uprisings and rebellions. This fear was not unfounded; history is replete with instances of slave rebellions, both attempted and actualized.

To mitigate this perceived threat, stringent gun control measures were instituted. Slaves, being considered property rather than people, were denied many rights, including the right to bear arms.

But, the fear did not stop with enslaved Black people. Even free Black Americans—those who had secured their freedom or were born free—were viewed with suspicion and often lumped together with their enslaved counterparts in the minds of white colonists. As such, they, too, faced prohibitive laws that barred them from owning or bearing firearms.

The antebellum South, with its sprawling plantations and deeply entrenched racial hierarchies, was particularly rigorous in its enforcement of these gun control laws. The mere thought of armed black individuals, whether free or enslaved, was enough to stoke the fears of a white populace already anxious about maintaining control over an increasingly large enslaved population.

Thus, laws were meticulously crafted and enforced to ensure that slaves and free Black Americans had limited, if any, access to firearms.

Image: Discovery of Nat Turner: wood engraving illustrating Benjamin Phipps's capture of Nat Turner (1800-1831) on October 30, 1831.

This was a deliberate move to maintain the status quo, prevent potential uprisings, and keep the power firmly in the hands of the white elite.

So, in essence, the earliest iterations of gun control in the U.S. were not just about firearms; they were deeply intertwined with issues of race, power, and control.

They served as tools to suppress certain groups, ensuring that the balance of power favored European settlers and, later, white Americans.

This foundation laid the groundwork for the complex issue of gun control debates that would unfurl in the centuries to come.

The 1960s were a tumultuous period in American history, characterized by profound societal change and transformation. The era saw the nation grappling with its history of racial discrimination, as the Civil Rights Movement sought to dismantle the entrenched systems of legal segregation and discrimination against Black Americans.

Sit-ins, marches, and speeches became synonymous with the decade, but alongside these nonviolent approaches, there were those who believed in a more radical form of activism.

Enter the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, established in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in the urban setting of Oakland, California.

While the broader Civil Rights Movement, led by figures like Martin Luther King Jr., emphasized nonviolent protest, the Black Panthers took a different approach.

Influenced by Marxist ideology and revolutionary ideals, they positioned themselves as a socialist organization, fervently advocating for the self-defense of African Americans against systemic oppression.

The Black Panthers believed that Black Americans had an inherent right to protect themselves from a government and policing system that they perceived as deeply and intrinsically racist.

This belief wasn’t unfounded. Events like the Watts Riots in 1965 underscored the tense relationship between the black community and law enforcement.

In this charged atmosphere, Newton and Seale saw the need for an organized, armed response to combat the institutional racism they felt was endemic in American society.

Image: Black Panther Party founders Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton standing in the street, armed with a Colt .45 and a shotgun

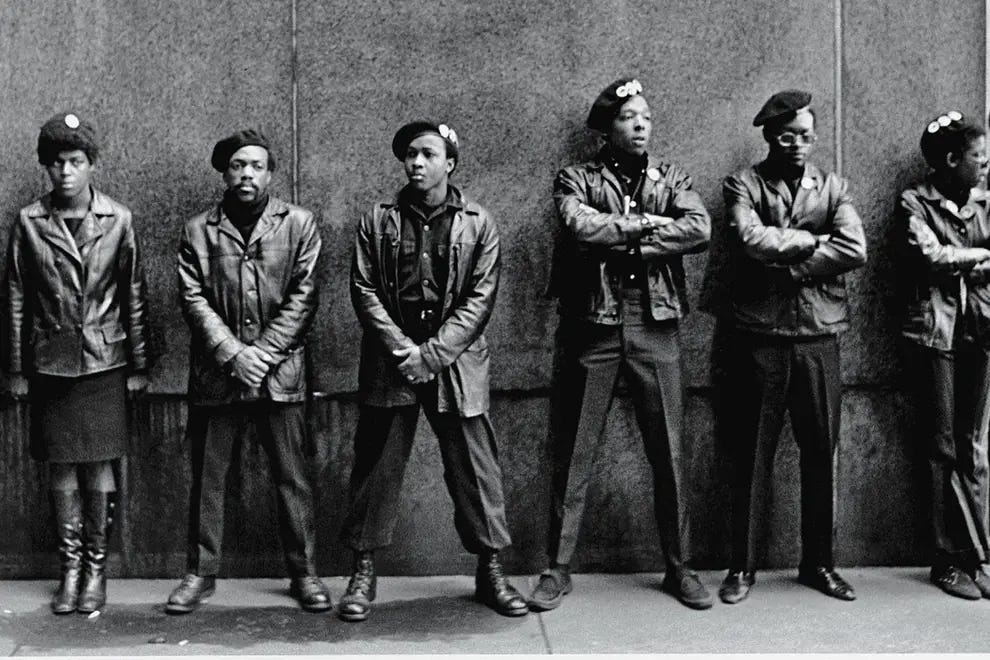

Among the many activities the Black Panthers engaged in, their “copwatching” patrols stand out as one of the most audacious. These patrols saw Black Panther members shadowing police officers in their communities.

But they weren’t merely passive observers; they were equipped with law books, cameras, and, most notably, legally owned firearms.

Their goal was multifaceted: to ensure that African Americans knew their rights during police interactions, to document instances of police misconduct, meant to serve as a deterrent to potential police brutality.

The copwatching patrols were more than a protective measure; they were a form of political theatre.

In a society where Black Americans were often marginalized and rendered invisible, the Black Panthers made themselves decidedly visible, demanding recognition and respect. In doing so, they redefined notions of black empowerment and resistance, ensuring their place in the annals of American history.

Central to the Panthers' strategy against racial injustice was the emphasis on firearm ownership and proficiency. From the early days, Newton and Seale accumulated an arsenal, ranging from machine guns to handguns. New members were not only trained in firearm handling and maintenance but were also educated on their legal rights regarding firearm possession, particularly when interacting with California law enforcement. Adam Winkler, the author of "Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms," notes that "Bobby Seale and Huey Newton invoked the Second Amendment to validate their public display of firearms as a means to monitor law enforcement."

During such patrols, the Panthers, armed and vigilant, would vocally advise individuals on their rights, emphasizing their right to silence. They assured the public that, should any injustice occur, the Black Panthers would intervene for their protection.

To further amplify their message against perceived governmental overreach on firearm rights, they orchestrated a notable demonstration at the state Capitol. On May 2, 1967, a gathering of eighth-graders was set to enjoy lunch with Governor Ronald Reagan on the west lawn of the Sacramento state capitol. Their plan was to dine on fried chicken and later explore the granite building designed to echo the national Capitol's look. However, their plans were disrupted when 30 young black men and women arrived, brandishing weapons such as .357 Magnums, 12-gauge shotguns, and .45-caliber pistols.

Image: Members of the Panthers are met on the steps of the State Capitol in Sacramento, May 2, 1967, by Police Lt. Ernest Holloway, who informs them they will be allowed to keep their weapons as long as they cause no trouble and don’t disturb the peace.

Upon reaching the capitol steps, Bobby Seale began to read from a statement:

“The American people, in general, and the black people, in particular, must take careful note of the racist California legislature aimed at keeping the black people disarmed and powerless. Black people have begged, prayed, petitioned, demonstrated, and everything else to get the racist power structure of America to right the wrongs which have historically been perpetuated against black people. The time has come for black people to arm themselves against this terror before it is too late.”

After reading, Seale told his companions, “All right, brothers and sisters, come on. We’re going inside.” Without any hindrance from metal detectors, Seale, along with the group, entered California's central government building, their loaded weapons with them.

The sight of Black activists standing inside the Capitol, weapons loaded and clearly visible, was a striking scene. It was more than a mere protest; it was a pointed statement on their Second Amendment rights and a challenge to the very lawmakers who were attempting to curtail those rights. The Panthers’ message was clear: they would not be silenced, and they would not be disarmed without a fight. The Black Panther Party’s method of armed self-defense was groundbreaking for its era. The unprecedented sight of organized black individuals, bearing arms and monitoring police officers, was not only an assertion of their Second Amendment rights but also a potent statement about black agency and autonomy.

This bold stance directly challenged the traditional power dynamics in American society. Police officers, typically symbols of authority, found themselves observed and held accountable by the very community they were meant to protect. Given the profound impact and disruption to the status quo, it was inevitable that lawmakers would soon respond to the Panthers’ radical approach.

But things backfired.

California became the epicenter of a legislative response to the Panthers’ activities with the proposal of the Mulford Act. This bill, introduced by Republican assemblyman Don Mulford, sought to prohibit the open carrying of loaded firearms in public spaces, effectively targeting the very core of the Panthers’ copwatching patrols. To many observers, the timing and intent of the Mulford Act were clear:

it was a legislative maneuver aimed to stop the Black Panther Party.

With support from the NRA, Mulford's bill, which not only repealed open carry laws in California but also prohibited firearms within the Capitol, swiftly passed both the Assembly and Senate. Governor Reagan, upon ratifying the law on July 28, expressed his inability to understand why civilians would need to carry loaded weapons on the streets.

This 1967 legislation, which banned the open carry of loaded firearms, steered California towards implementing some of the country's strictest gun control measures and sparked momentum for more comprehensive national gun control efforts. Mulford had adeptly capitalized on the prevailing apprehension white Americans held toward Black-Americans in the 1960s, thereby diminishing the power the Black Panthers derived from their firearms. But, as Winkler points out, while the legislation curtailed the Black Panthers, it didn't markedly curb criminal violence.

Image: Guns and ammunition seized by Oakland and Berkeley police in the 1974 arrest of 14 Black Panthers

The NRA's support for this gun control measure wasn't an isolated instance. Initially established in 1871 to enhance the marksmanship skills of Civil War veterans, the NRA had backed gun control measures in the past. During the 1920s and 1930s, they supported limitations on public firearm carry to alleviate anxieties about European immigrants, who often carried weapons openly. Post the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, the NRA endorsed the Gun Control Act, which imposed strict restrictions on gun purchases based on several criteria, including mental health and age.

Winkler notes that the Mulford Act was among several enacted during the late 1960s that aimed at regulating firearms, often with a particular focus on the Black-American community. This included the Gun Control Act of 1968, which introduced prohibitions against specific individuals owning guns, intensified licensing and oversight of gun dealers, and curbed the import of inexpensive "Saturday night specials" (compact pistols) prevalent in certain urban areas. Unlike the NRA's staunch stance against gun control in contemporary America, the group advocated for more stringent gun regulations in the 1960s. This push was largely motivated by a desire to prevent Black-Americans from possessing firearms amidst rising racial tensions. The Black Panthers, known for their highly-publicized open carrying of firearms in California where it was legal, particularly alarmed the NRA.

The Second Amendment of the United States Constitution remains one of its most debated and ambiguous provisions. Paraphrasing, it generally declares that a well-regulated military, being necessary for the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be altered. Some interpret this as a guarantee of an absolute right for American citizens to possess guns, emphasizing the "right to bear arms." In contrast, others believe it ensures this right only within the context of a well-regulated armed force. Interestingly, the Black Panthers positioned themselves at the intersection of these two interpretations.

The Black Panthers were “innovators” in the way they viewed the Second Amendment at the time, says Winkler. Rather than focus on the idea of self-defense in the home, the Black Panthers brazenly took their weapons to the streets, where they felt the public—particularly Black-Americans—needed protection from a corrupt government.

These ideas eventually infiltrated into the NRA to shape the modern gun debate, explains Winkler. As gun control laws swept the nation, the organization adopted a similar stance to that of the activist group they once fought to regulate, with support for open-carry laws and concealed arms laws high on their priorities. For many in America, particularly those in marginalized communities, the right to bear arms was perceived as a means of self-defense against oppressive forces.

Image: Black Panther Party members stand in protest outside a New York City courthouse, April 11, 1969

Image: Black Panther Party members stand in protest outside a New York City courthouse, April 11, 1969

The Panthers adopted this stance but added a layer of organized resistance. They didn’t just arm themselves as individuals; they organized patrols, educated community members about their rights, and openly carried their weapons as a collective show of force and solidarity.

While the rhetoric surrounding gun control often hinges on the need to ensure public safety, the history of firearm regulation in the U.S. tells a more nuanced story. In instances like the Mulford Act, it becomes evident that gun control measures can, at times, be influenced by deeper political and racial anxieties. The Black Panther Party, with its revolutionary ethos and advocacy for armed self-defense, profoundly challenged the established order, emphasizing the racial and political tensions inherent in American society. Their presence and the subsequent legislative response underline that gun control discussions extend beyond just weaponry; they touch upon themes of power, control, and apprehension towards societal shifts. Historically, while gun control measures often cite public safety, they have sometimes been used to suppress or control particular racial or political groups. This highlights the need to delve deeper into the motivations behind these regulations and grasp the wider sociopolitical landscapes from which they emerge.

Resources

https://www.history.com/news/black-panthers-gun-control-nra-support-mulford-act

https://www.pbs.org/hueypnewton/actions/actions_capitolmarch.html

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/09/the-secret-history-of-guns/308608/

Books

Certainly. Here are the Chicago style citations for the provided books in alphabetical order without numeration:

Adams, Les. *The Second Amendment Primer. A Citizen's Guidebook To The History, Sources, And Authorities For The Constitutional Guarantee Of The Right To Keep And Bear Arms*. Birmingham, Alabama: Odysseus Editions, 1996.

Anderson, Carol. *The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America*. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021.

Carter, Gregg Lee. *Gun Control in the United States: A Reference Handbook*. ABC-CLIO, 2006.

Davidson, Osha Gray. *Under Fire: The NRA and the Battle for Gun Control*. University of Iowa Press, 1998.

Edel, Wilbur. *Gun Control: Threat to Liberty or Defense against Anarchy?* Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 1995.

Goss, Kristin A. *Disarmed: The Missing Movement for Gun Control in America*. Princeton University Press, 2008.

Halbrook, Stephen P. *Gun Control in the Third Reich: Disarming the Jews and "Enemies of the State"*. Independent Institute, 2013.

Hampton, Henry, and Steve Fayer. "Birth of the Black Panthers, 1966–1967." In *Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s Through the 1980s*. Random House, 2011.

Lund, Nelson. "Right to Bear Arms." In *The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism*, edited by Ronald Hamowy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute, 2008.

Melzer, Scott. *Gun Crusaders: The NRA's Culture War*. New York University Press, 2009.

Snow, Robert L. *Terrorists Among Us: The Militia Threat*. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus, 2002.

Umoja, Akinyele Omowale. *We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement*. NYU Press, 2013.

Utter, Glenn H. *Encyclopedia of Gun Control and Gun Rights*. Phoenix, Ariz.: Oryx, 2000.

Winkler, Adam. *Gunfight: The Battle over the Right to Bear Arms in America*. W. W. Norton & Company, 2011.