Image: A sculpture by Kwame Akoto-Bamfo at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Source: Equal Justice Initiative, https://eji.org/report/transatlantic-slave-trade/new-england/#a-trafficking-based-economy

The idea of a beginning is never neutral.

A nation decides where its story begins not to clarify the past, but to command the present. The year 1776 was not chosen because it was true. It was chosen because it was useful. It cast liberty as origin, slavery as deviation. And in doing so, it allowed forgetting to become a civic virtue.

But forgetting is not benign. It is a strategy.

And in August of 2019, something interrupted that strategy.

No government issued it. No textbook committee approved it. No university press bound it in cloth. It arrived in a magazine—paper, ink, and a date that made no gesture toward forgetting. That date was 1619.

It was not a legal claim. It did not say the nation was born in bondage rather than independence. What it said—plainly—was that the ideals Americans claim to honor were inseparable from the realities they preferred to obscure. That Black Americans had not been passengers in the American story but its relentless agents. Not its beneficiaries, but its builders.

This claim did not pass unnoticed.

Image: An 1847 ad placed by Nautilus Mutual Life Insurance (later renamed New York Life Insurance) offering insurance policies on enslaved people.” The Daily Democrat,. Source: EJI, https://eji.org/report/transatlantic-slave-trade/new-england/#industries-reliant-on-enslaved-labor

Some objected to the evidence. Some debated the footnotes. They challenged whether the Revolution was sparked, even in part, by a desire to protect slavery. Whether capitalism itself could be traced to sugar and cotton and debt. These were fair questions. The Project invited them.

But that wasn’t the source of the backlash.

The problem wasn’t the claim. It was the claimant.

Image: Nikole Hannah-Jones, Source: Alice Vergueiro/Wikimedia Commons.

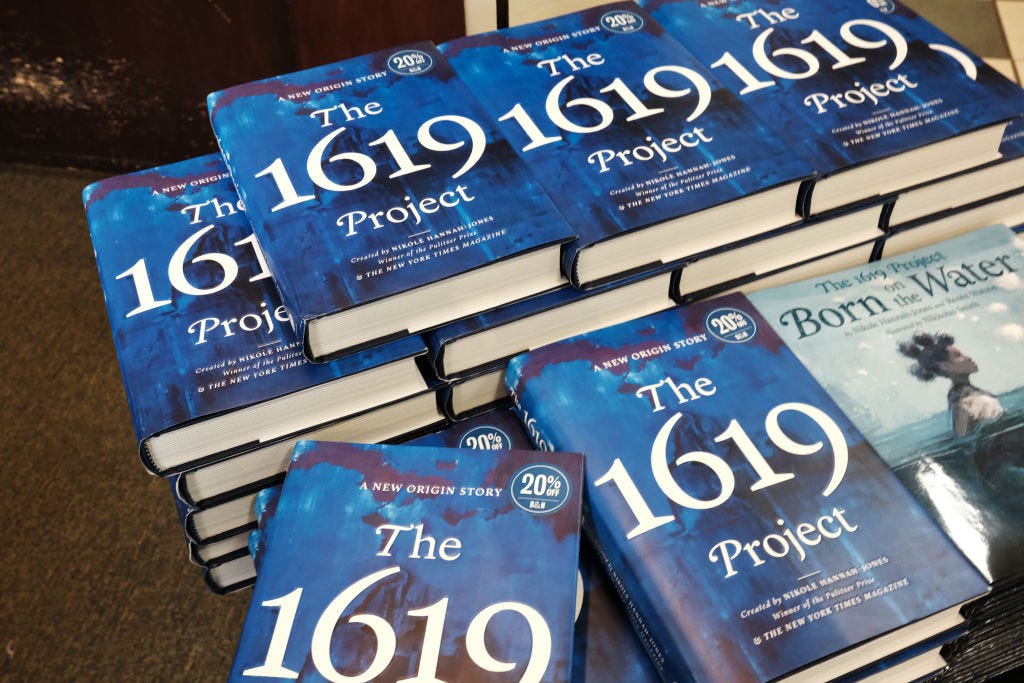

Image: The book by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story” is displayed at a New York City bookstore on November 17, 2021 in New York City. First published in The New York Times Magazine, “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story” was written to center the effects of slavery and the achievements of Black people in the history of the United States. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

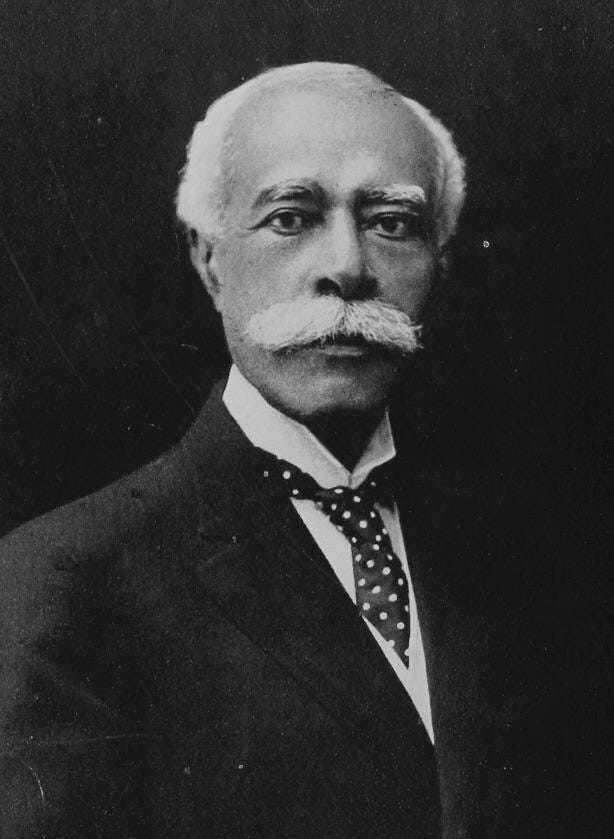

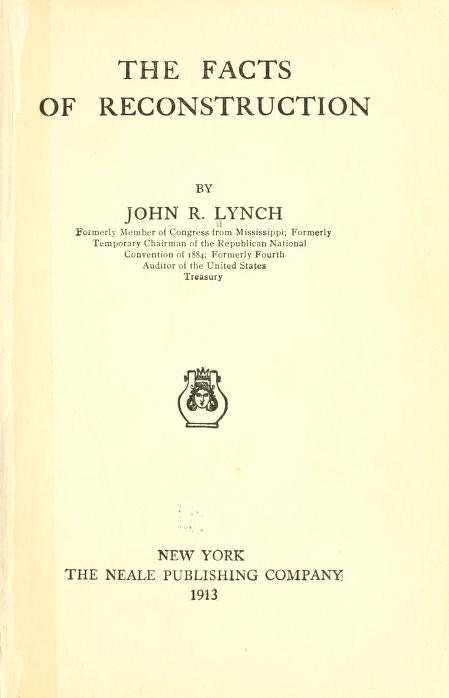

It had happened before. In 1913, when a congressman named John Roy Lynch tried to set the record straight in The Facts of Reconstruction. Lynch had lived it. He had fought for it. But it was a Boston historian named James Ford Rhodes whose version prevailed. Rhodes had not lived it. But he was white. He was called “objective.” And that, in the archives of American memory, was enough.

Image: Congressman John Roy Lynch before 1920, Source: Library of Congress.

Image: Lynch, John Roy. The Facts of Reconstruction. New York, The Neale Publishing Company, 1913. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/14000471/.

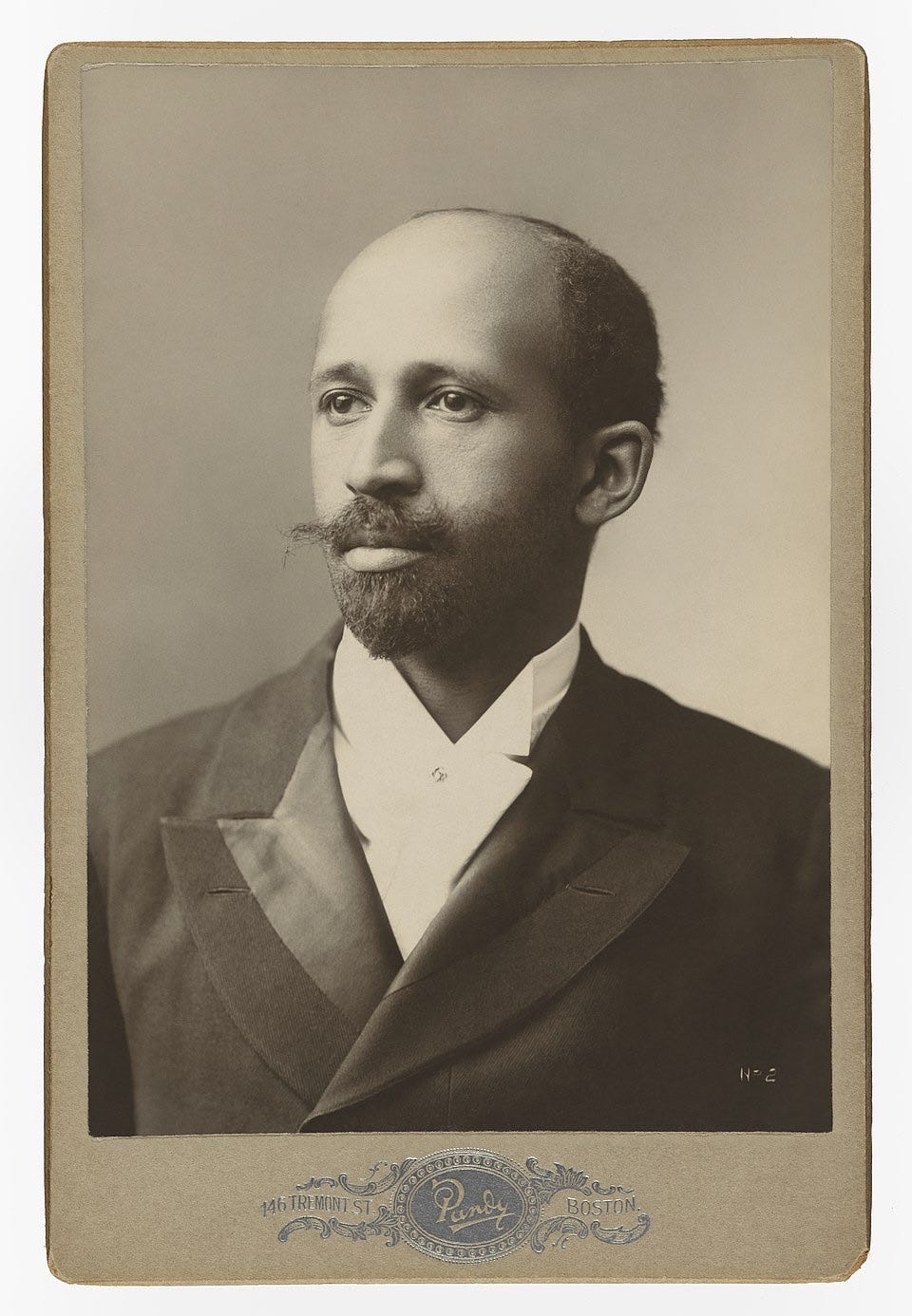

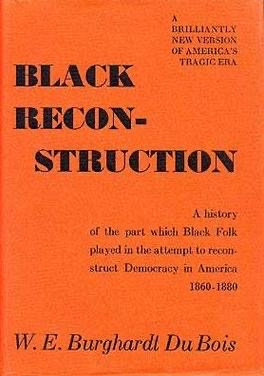

It happened again in 1935. Du Bois wrote Black Reconstruction in America, a masterwork—its logic meticulous, its research colossal. But the academy held the door half-open. His conclusions were “moral,” his tone “political.” The truth he offered came too soon.

Image: W.E.B. Du Bois by James E. Purdy, 1907, gelatin silver print, Source: the National Portrait Gallery. (https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.80.25) Gelatin silver print.

Image: Black Reconstruction in America, 1st Edition cover. Source: https://archive.org/details/blackreconstruc00dubo/mode/1up

And again in the 1960s. Howard Zinn, whose People’s History told of slaves and workers and mothers and immigrants, was labeled a polemicist. Too passionate, too partial, too alert to the consequences.

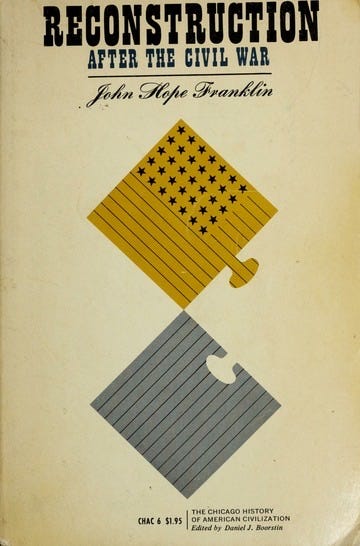

Even John Hope Franklin, with his dignified cadence and command of the archive, was treated not as a peer, but an exception. He was allowed in—but reminded, always, that the invitation was conditional.

Image: John Hope Franklin in 1956. Source: Associated Press.

Image: Reconstruction After the Civil War, 1st Edition. Source: https://archive.org/details/reconstructionaf00fran

So when the 1619 Project arrived—not from a university but from The New York Times—it was not an aberration. It was an inheritance.

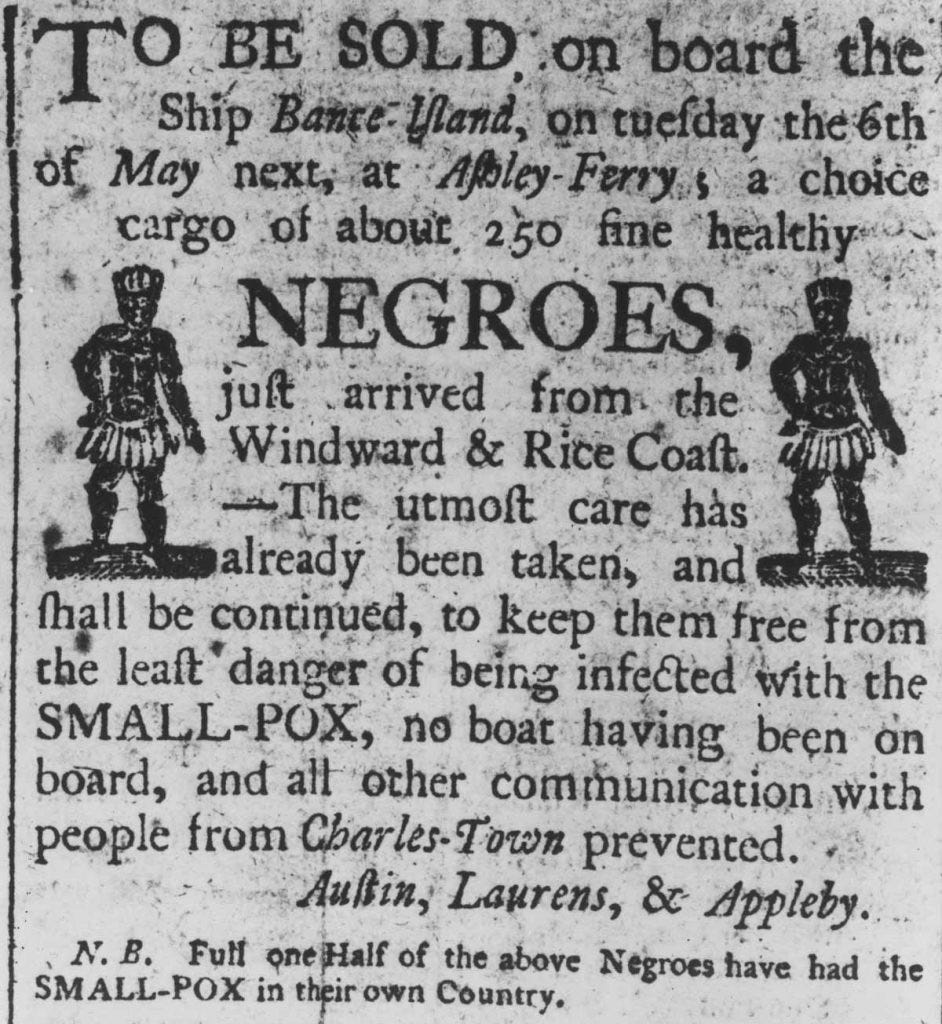

Image: An advertisement for the sale of roughly 250 enslaved people trafficked into Boston on the Bante Island ship, ca. 1700. Source: https://eji.org/report/transatlantic-slave-trade/boston/#the-port-of-boston

And its power was not just in its content. It was in its placement. It did not whisper from the margins. It declared, from the nation’s most influential paper, that America’s founding contradiction was not incidental. It was structural.

That was the rupture.

State legislatures called it dangerous. Editorial boards called it dishonest. But what they meant was something more elemental: it was unsanctioned. It had spoken with authority not granted, but claimed.

The story of a nation is never just about events. It is about meaning. And meaning is always contested. At stake is not just what happened, but who is allowed to say what it meant.

That was what made 1619, to its critics, intolerable.

It refused to defer. It refused to pretend that the ideals of the republic had ever stood cleanly apart from the profits of bondage. It refused to pretend that the silence had ever been neutral. And so it spoke. Clearly. Publicly.

Image: mprisoned men at Maula Prison in Malawi who were forced to sleep “like the enslaved on a slave ship.” Joao Silva/The New York Times/Redux.

The truth had never been hidden. Only downgraded. Deferred. Denied primacy.

What the Project did was simple: it named the contradiction at the heart of the republic. And it did so not in the voice of apology, but with the authority of those who had lived it.

It did not erase 1776.

It completed it.

And in doing so, it crossed a line invisible to many—but real. A line that, once crossed, changed not just the record, but who is allowed to write it.

Primary Sources

Bynum, Victoria, James M. McPherson, James Oakes, Sean Wilentz, and Gordon S. Wood. “Letter to the Editor.” The New York Times Magazine, December 2019.

Hannah-Jones, Nikole. “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written. Black Americans Have Fought to Make Them True.” The New York Times Magazine, August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/black-history-american-democracy.html.

Harris, Leslie M. “I Helped Fact-Check the 1619 Project. The Times Ignored Me.” Politico Magazine, March 6, 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/03/06/1619-project-new-york-times-mistake-122248.

Silverstein, Jake. “We Respond to the Historians Who Critiqued the 1619 Project.” The New York Times Magazine, December 20, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/20/magazine/we-respond-to-the-historians-who-critiqued-the-1619-project.html.

Silverstein, Jake. “An Update to The 1619 Project.” The New York Times Magazine, March 11, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/magazine/an-update-to-the-1619-project.html.

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804. New York: W. W. Norton, 2016.

Waldstreicher, David. Slavery’s Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification. New York: Hill and Wang, 2009.

Jackson, Lauren Michele. “The 1619 Project and the Demands of Public History.” The New Yorker, December 8, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/12/13/the-1619-project-and-the-demands-of-public-history.

Painter, Nell Irvin. “How We Think About the Term ‘Enslaved’ Matters.” The Guardian, August 14, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/aug/14/slavery-in-america-1619-first-ships-jamestown.

Railton, Ben. “Trump’s ‘Patriotic Education’ Commission Yet Another Battle Over the Meaning of Those Words.” History News Network, September 20, 2020. https://www.historynewsnetwork.org/article/trumps-patriotic-education-commission-yet-another-.

Serwer, Adam. “The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts.” The Atlantic, December 23, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/12/historians-clash-1619-project/604093/.

Waldstreicher, David. “The Hidden Stakes of the 1619 Controversy.” Boston Review, January 24, 2020. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/david-waldstreicher-hidden-stakes-1619-controversy/.

Secondary Sources

Lepore, Jill. These Truths: A History of the United States. New York: W. W. Norton, 2018.

Berlin, Ira. Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003.

———. Liberty Tree: Ordinary People and the American Revolution. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

———. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998.

———. Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South. New York: New Press, 1974.

———. The Long Emancipation: The Demise of Slavery in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

———. The Making of African America: The Four Great Migrations. New York: Viking, 2010.

———, and Gregory H. Nobles. Whose American Revolution Was It?: Historians Interpret the Founding. New York: New York University Press, 2011.

Dunbar, Erica Armstrong.

Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge. New York: Atria Books, 2017.

Frey, Sylvia R.

Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Gordon-Reed, Annette.

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. New York: W. W. Norton, 2008.

Holton, Woody.

Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves, and the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Gary B. Nash, Red, White, and Black: The Peoples of Early America. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1974.

Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution. Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture by the University of North Carolina Press, 1961.

———. The Negro in the Making of America. 3rd ed. Revised, Updated, and Expanded. New York: Collier Books, 1987.

Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 Through the Stono Rebellion. New York: W. W. Norton, 1974.

Carter G. Woodson, The History of the Negro Church. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1921.

———. The Mis-Education of the Negro. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1933.

———. The Negro in Our History. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1922.

Benjamin Quarles, Black Abolitionists. New York: Da Capo, 1969.

Benjamin Quarles, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, 1st edn New York: A. A. Knopf, 1947. Last updated by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, 9th edn. McGraw-Hill Education, 2010.

John Hope Franklin, The Militant South, 1800–1861. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1956; 1st Illinois pbk. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

John Hope Franklin, Reconstruction: after the Civil War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

John Hope Franklin, The Emancipation Proclamation. 1st edn. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1963; 2nd edn. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1993.

John Hope Franklin,Land of the Free; A History of the United States, by John W. Caughey, John Hope Franklin and Ernest R. May. Educational advisers: Richard M. Clowes and Alfred T. Clark Jr. Rev. New York: Benziger Bros., 1966.

John Hope Franklin, Color and Race, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1968.

John Hope Franklin,The Historian and Public Policy, Chicago: University of Chicago, Center for Policy Study, c1974.

John Hope Franklin,A Southern Odyssey: Travelers in the Antebellum North, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, c1976.

John Hope Franklin,Race and History: Selected Essays 1938–1988, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, c1989.

John Hope Franklin,The Facts of Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of John Hope Franklin, edited by Eric Anderson & Alfred A. Moss Jr. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, c1991.

John Hope Franklin, Racial Equality in America, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1993.

John Hope Franklin,My Life and an Era: the Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin, edited by John Hope Franklin and John Whittington Franklin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, c1997, 2000.

John Hope Franklin,Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation, John Hope Franklin, Loren Schweninger. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1975.

Leslie M. Harris, Slavery and the University: Histories and Legacies, co-edited with James T. Campbell and Alfred L. Brophy (University of Georgia Press, 2019) ISBN 9780820354422

Leslie,M Harris,Slavery, emancipation, and class formation in colonial and early national New York City (Journal of Urban History, 2004).

Davis, David Brion. From Homicide to Slavery: Studies in American Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

———. Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

———. Slavery and Human Progress. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984. Paperback edition, 1986.

———. Slavery and the Idea of Progress. Jackson: Center for the Study of Southern Culture and Religion, 1979.

———. Slavery in the Age of Emancipation. New York: Knopf, 2014.

———. Slavery in the Colonial Chesapeake. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1986.

———. The Antislavery Debate: Capitalism and Abolitionism as a Problem in Historical Interpretation. Edited by Thomas Bender. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

———. The Emancipation Moment. Gettysburg: Gettysburg College, 1984.

———. The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1966.

Harris, Leslie M., and Daina Ramey Berry, eds. Sexuality and Slavery: Reclaiming Intimate Histories in the Americas. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.