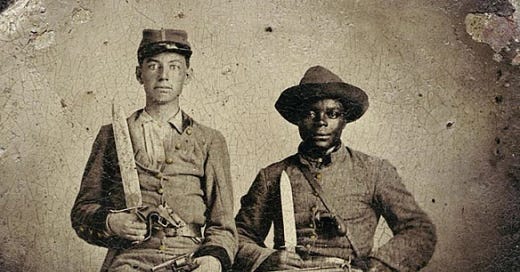

Image: Image: Andrew Chandler and his enslaved body servant, Silas.

There is an iconic photograph that has become a cornerstone in the online world of the Neo- Confederacy. This image, and its thousands strong replicas, captures a black man barely out of adolescence in what resembles a confederate uniform. He sits stoically beside his fresh faced companion, suggesting the two are of singular purpose—-comrades in arms.

Andrew and Silas Chandler have a story that is both unique and representative of the complex relationships that existed during the American Civil War era. Andrew was a white Confederate soldier from Mississippi, and Silas was an enslaved Black American man owned by Andrew's family.

Before the Civil War, Andrew and Silas were raised together on the Chandler family plantation in Mississippi. Their relationship, though deeply unequal due to the institution of slavery, was reported by the White Chandlers to be close.

When the Civil War broke out, Andrew enlisted in the Confederate army. As was common at the time, he brought Silas with him, not as a fellow soldier, but as his enslaved servant. Silas' role was to assist Andrew, which included tasks like setting up camp, cooking, and tending to Andrew's needs.

The most famous aspect of their story comes from the photograph taken in 1861. In it, Andrew, in his Confederate uniform, is seated, while Silas sits beside him wearing a forage cap and a "body servant" uniform, signifying his status as an enslaved servant accompanying a soldier. This image has often been used to support various narratives about the war and the role of Black Americans in the Confederacy.

According to mythology , during the war, Andrew was wounded, and Silas reportedly played a crucial role in getting him to safety and ensuring his recovery. This act has been cited to suggest loyalty and friendship between the two, although it's crucial to remember the context of Silas's enslaved status and lack of freedom to choose his actions independently.

The Confederacy’s loss emancipated Silas. He eventually acquired land near the Chandlers and became a successful farmer. The families remained in contact, and Silas' descendants have attended Chandler family reunions.

The story of Andrew and Silas Chandler is often brought up in discussions about the Civil War and the complex relationships between enslaved people and their enslavers. It's a narrative that defies simple categorization, reflecting the intricacies and contradictions of personal relationships under the shadow of slavery and war.

This narrative is the myth of the Black confederate.

The story of Andrew and Silas Chandler is often entangled with the broader myth of the "Black Confederate." This myth suggests that a significant number of Black American slaves and free blacks voluntarily fought for the Confederacy during the American Civil War, often as soldiers.

Image: An artist’s mythological interpretation of Silas and Andrew Chandler.

In reality, Silas, like virtually all Black Americans who served the Confederacy, were slaves, not soldiers, a crucial detail often overlooked in the narrative. This misrepresentation obscures the complex and often painful truths of history, replacing them with a simplified and inaccurate account.

The narrative of the Black soldier is largely a misrepresentation of historical facts and is used by neo-Conderates to downplay the centrality of slavery as the cause of the Civil War and to present a more benign image of the Confederacy.

What most Black folks know intrinsically but many White Americans have to learn in books, is that many enslaved men, like Silas Chandler, accompanied their enslavers to war. But, they were there as bodyservants, not as armed soldiers. Their roles were to cook, clean, and perform other menial tasks. Any depiction of them as willing combatants is misleading.

Enslaved people like Silas had NO choice in their situation. Their presence in Confederate camps was a result of the bondage and coercion inherent in slavery, not an indication of their support for the Confederate cause.

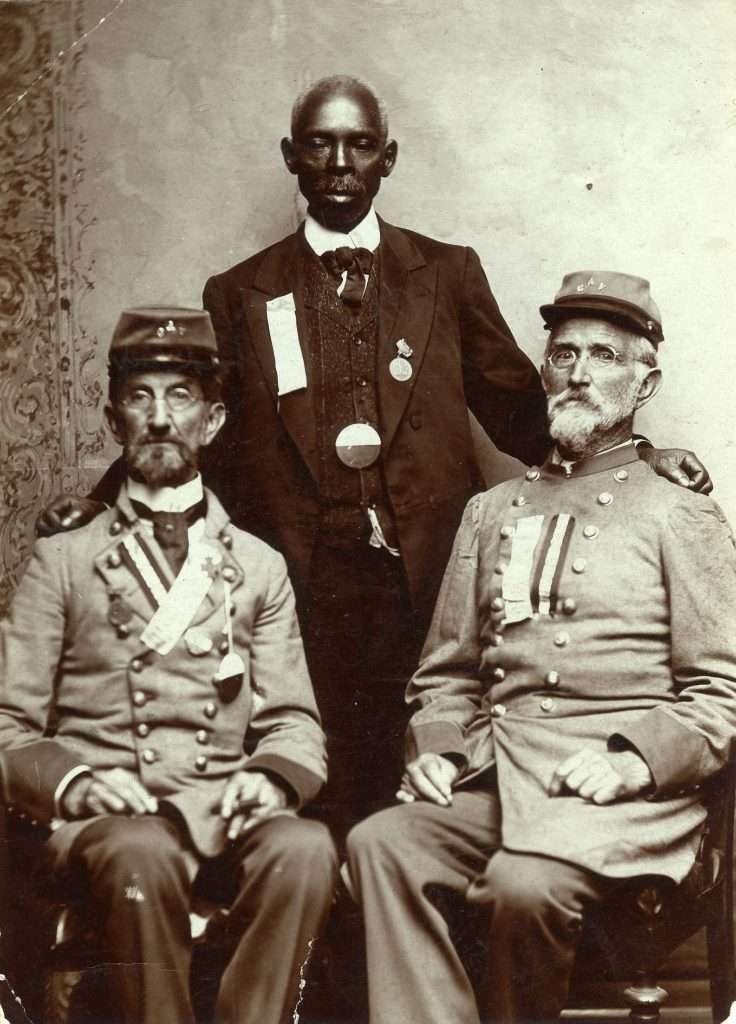

Image: 3 men named Ellis, 1907. The image conveys the Lost Cause point of view that accentuates the role of African Americans as "faithful slaves," loyal to their masters and the Confederate cause.

Indeed , the Confederacy, for the majority of the war, explicitly prohibited the enlistment of Black men as soldiers. It was only in the final months of the war, when the South was facing imminent defeat, that a policy to enlist slaves was passed, but even then, as desperate as the Confederacy was, the measure barely implemented.

And, despite their loyal service in providing for and facing just as much danger as their enslavers, it was the Union victory (including hundreds of thousands is US Colored Troops) that freed the enslaved, not “benevolent “ grateful slave owners.

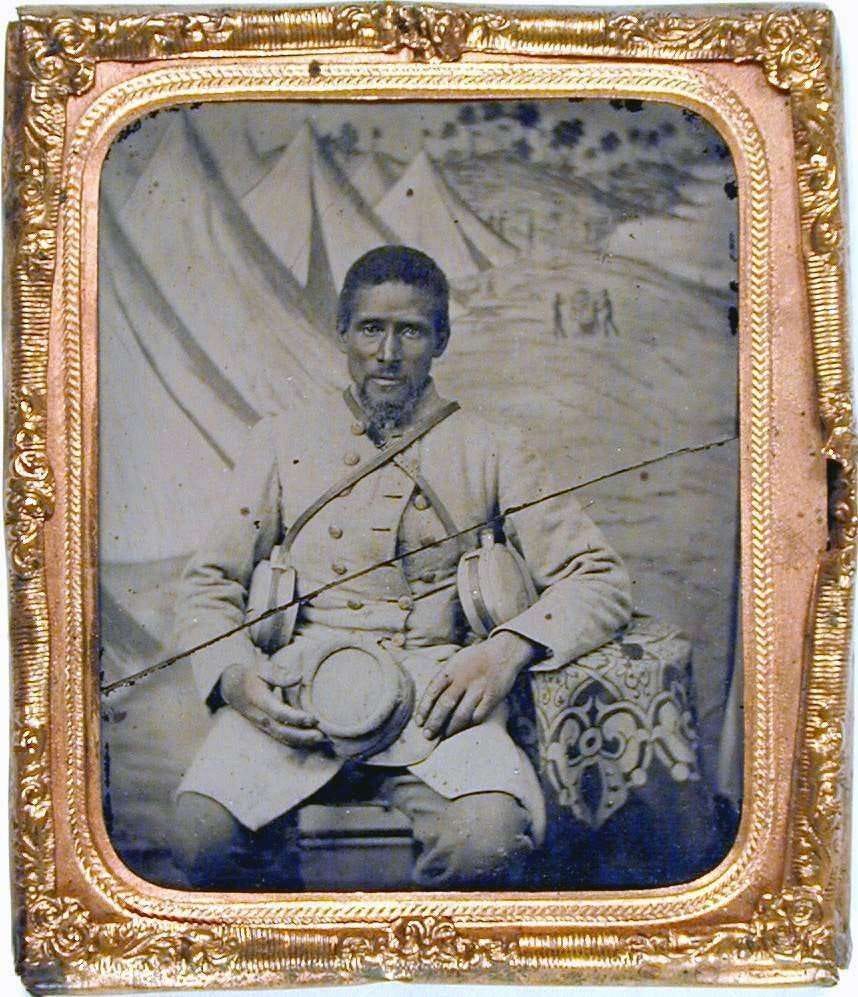

Image: Marlboro Jones, manservant of Confederate captain Randal F. Jones of the 7th Georgia Cavalry, sits for an ambrotype dressed in Confederate uniform. Captain Jones was killed in battle. Marlboro accompanied his body home.

When the Civil War concluded in 1865, Silas Chandler found his way back to Mississippi, to a life he had left behind. There, he reunited with his wife Lucy and met his son William, born while Silas was away. Together, Silas and Lucy raised twelve children, though only five reached adulthood.

Silas, with his remarkable carpentry skills, became a well-known figure in West Point, Mississippi. He passed on his trade to at least four of his sons, collaborating with them on numerous projects. Their craftsmanship was evident in the finest structures of West Point, including houses, churches, and banks, showcasing their talent across the state.

In 1868, Silas, alongside other former slaves, constructed a simple altar for their Baptist congregation, a testament to their faith and resilience. This humble beginning later evolved into a wood-frame church, with Silas's son William contributing to a new church building on the same site in 1896.

Image: Slave/Body Servant with Confederate Captain (c. 1862-65.

Remaining an active Baptist and Mason, Silas lived close to Andrew and his brother, Benjamin Chandler, both of whom had prospered as farmers. Benjamin passed away in 1909, and Silas followed a decade later at the age of eighty-two in September 1919. Andrew outlived Silas by merely eight months, dying in May 1920.

In 1994, a century after the end of the Civil War, the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy held a ceremony at Silas's grave, acknowledging his service during the war. This tribute, marked by an iron cross and flag at his gravesite, elicited mixed feelings among the Chandler family members, both black and white.

Reflecting on her great-grandfather's legacy, Myra Chandler Sampson expressed a critical view. She saw Silas as a man coerced into a conflict contrary to his beliefs, dressed in a Confederate uniform for reasons lost to time. Myra saw the ceremony as an attempt to romanticize and soften the harsh realities of American history, a narrative she vehemently opposed.

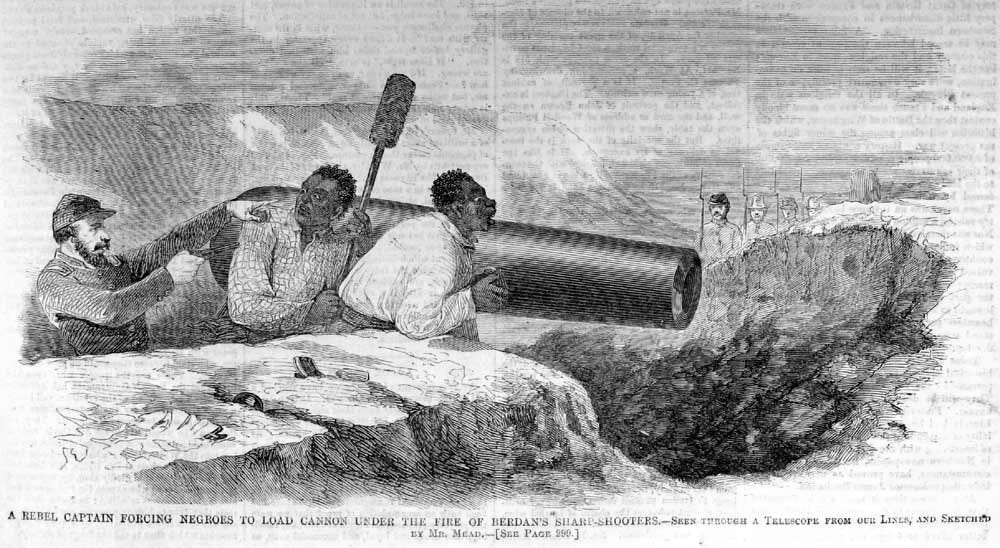

Image: An 1862 Harper’s Weekly caricature of black slaves being forced at gunpoint to load and fire a cannon against Federal troops.

The propagation of stories like that of Andrew and Silas, used to bolster the Black Confederate myth, typically glosses over the harsh realities of the era, particularly the context of slavery, the coercive environment, and the severely limited rights of African Americans during the Civil War.

While the Chandler story is indeed a part of Civil War history, its use to substantiate the myth of willing black soldiers fighting for the Confederacy is a distortion of historical realities. It overlooks the essential facts about slavery, the limited rights of black people during this period, and the actual policies of the Confederacy regarding black soldiers.

Next time: Bass Reeves, the legendary Deputy US Marshal. He was even braver than we know.

Resources

https://www.historicamerica.org/journal/2021/2/26/the-myth-of-the-black-confederate-soldier

https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/SoldierbiosChandler.html

https://amp.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/oct/13/black-confederates-civil-war-myth-kevin-levin

https://acwm.org/blog/myths-misunderstandings-black-confederates/

https://las.illinois.edu/news/2013-09-01/myth-black-confederates

https://www.nps.gov/chch/learn/news/clarkleeprogram2022.htm

Books

Coddington, Ronald S. African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Levin, Kevin M. Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. Illustrated edition. Civil War America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Bonekemper III, Edward H. The Myth of the Lost Cause: Why the South Fought the Civil War and Why the North Won. Civil War Collection. Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, 2022.

Maurantonio, Nicole. Confederate Exceptionalism: Civil War Myth and Memory in the Twenty-First Century. Illustrated edition. CultureAmerica. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2019.

Thank you for this!